FIELD TO JAR: PART 3

Peanut Protectors

UGA researchers work to develop innovative solutions to aflatoxin contamination in peanuts

On a warm morning in mid-September, tractor-drawn peanut-digging equipment burrowed beneath the peanut vines on the first of Tift County peanut farmer Greg Davis’s fields.

Spanning several rows, the digger inverted the vines, exposing the peanuts to the air and sun to dry the pods for several days above ground. Field workers then drove a peanut combine over the rows, picking up the plants and separating the peanut pods from the vines, dirt and debris from the field.

This is the day peanut producers — and University of Georgia Cooperative Extension agents and UGA peanut researchers — work all season for. But, even assuming a successful harvest, there is still a long way to go before peanuts are ready to be prepared as seed for the next year or sent for processing into a wide range of end products.

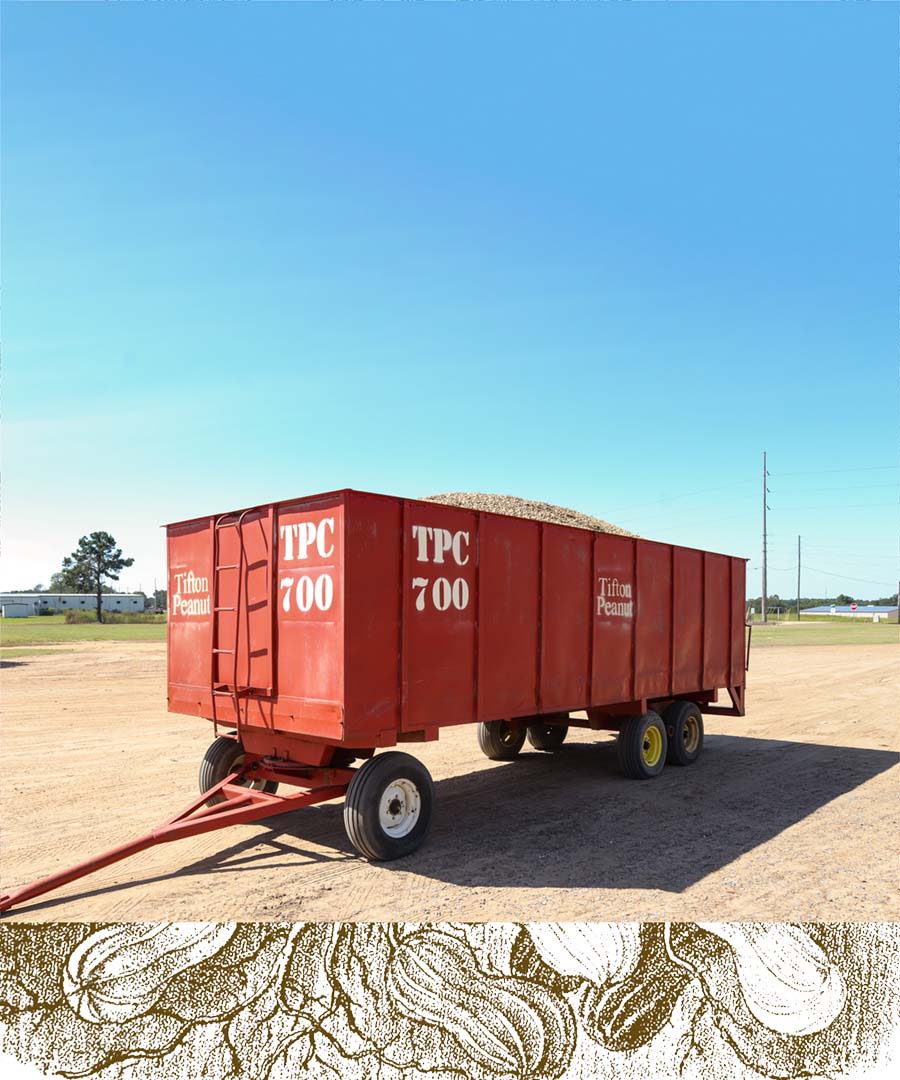

The first stop after harvest is a peanut-buying point, where peanuts are dried and graded by the Georgia Federal State Inspection Service, a multi-step process that starts with sampling 60 to 200 pounds of peanuts from each load, dependent on its size, and labeling them to document farm of origin, variety and other important identifying information needed to track each load throughout the process.

Those samples are taken into the peanut buying facility to be weighed, shelled, cleaned, separated by size, inspected for damage or disease, and graded according to U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) regulations.

A transport trailer containing a load of peanuts waits for inspection at a peanut shelling station in Tifton, Georgia. (Photo courtesy of the Georgia Peanut Commission)

A transport trailer containing a load of peanuts waits for inspection at a peanut shelling station in Tifton, Georgia. (Photo courtesy of the Georgia Peanut Commission)

A group of participants in the Georgia Peanut Tour watch an employee at Tifton Peanut Company inspect peanuts for quality.

A group of participants in the Georgia Peanut Tour watch an employee at Tifton Peanut Company inspect peanuts for quality.

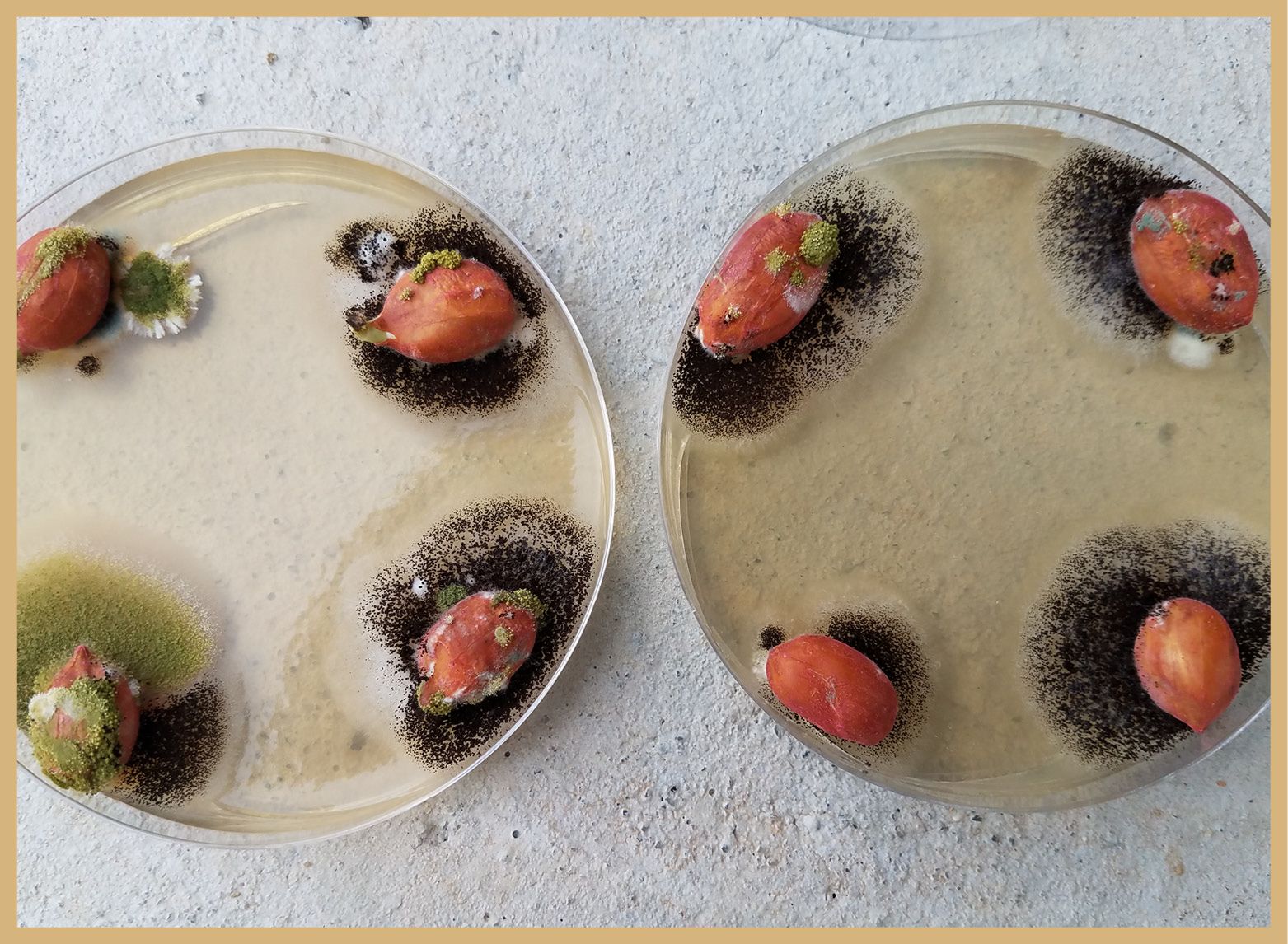

Aspergillus spp. grows on peanuts in petri dishes.

Aspergillus spp. grows on peanuts in petri dishes.

Fungal foe

A major source of concern for peanut producers is the presence of aflatoxin, a poisonous substance produced by the fungi Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus, which are naturally found on crops like peanuts, maize and grains. In peanuts alone, the industry-wide yield loss to aflatoxin in Georgia was estimated at 24% in 2019.

Many experts in the UGA College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences are working to address the global aflatoxin problem in peanut, including researchers in the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Peanut, who developed a course to increase basic knowledge of aflatoxin for producers in developing countries. A multidisciplinary team at UGA is currently working under a Presidential Interdisciplinary Seed Grant in the Georgia Aflatoxin Research and Mitigation Center of Excellence.

“Irrigated peanuts are much less likely to have aflatoxin, and Georgia is fortunate in that over half of our total production is from irrigated fields,” said Tim Brenneman, professor of peanut and pecan disease management in the CAES Department of Plant Pathology and a member of the UGA Peanut Team. “The biggest issue by far is in non-irrigated fields, especially in unusually hot, dry years like 2019 when losses were estimated at 24%.”

UGA researchers are working with the USDA’s National Peanut Research Laboratory in Dawson, Georgia, and industry partners on a multidisciplinary research project involving entomologists, crop physiologists, agriculture engineers, forestry experts, plant pathologists and others to come up with creative and innovative ways to reduce aflatoxin contamination in peanuts.

“UGA is taking a multidisciplinary approach and applying our different areas of expertise to come up with lasting solutions for growers,” said Bob Kemerait, professor and UGA Extension plant pathologist. “Aflatoxin may not be a major problem every year, but the fungus that causes it, Aspergillus flavus, is very common and is present in almost every field, so the potential is always there. While field rotation does work on some diseases, it’s difficult if not impossible to rotate away from Aspergillus flavus. If the conditions are right and we can’t mitigate, the aflatoxin problem will come back.”

From breeding to storage

The UGA team is exploring several potential methods to control aflatoxin. One option is improving peanut varieties with increased drought tolerance to reduce susceptibility or concentration of aflatoxin in peanuts. Another is control through production strategies such as irrigation, improved detection strategies, and preventing insect or other damage to peanut pods during the growing season.

“A significant area of new research is focused on trying to determine how we can better identify the areas in a field that are more likely to be at a higher risk for aflatoxin, for whatever reason,” Kemerait said. “If we can identify those areas of greater risk, we can apply management strategies to control it or perhaps modify a grower’s harvest plans.”

The team is also exploring the efficacy of biological control methods, such as Afla-Guard, a natural agent that includes a variant of Aspergillus flavus that does not produce aflatoxin. The hope is that the non-toxin-producing strains will outcompete the toxicogenic strain of the fungus in the peanut fields, Kemerait said.

Parallel research efforts include improving storage of harvested peanuts to reduce the potential for aflatoxins to proliferate during storage.

“A crop could have low aflatoxin levels going into storage, but if there is too much moisture in the storage area, peanuts that would have been at acceptable levels can develop high levels of aflatoxin,” Kemerait added. “Detection is absolutely essential. If you can detect whether a crop is above threshold levels or at risk for aflatoxin, you want to keep those peanuts away from peanuts with low levels or no aflatoxin. When you store peanuts, you have to store them appropriately so that even low levels of aflatoxin do not proliferate.”

In the peanut industry, much of each year’s harvest is put into storage to provide a steady supply of peanuts for the production demands of end users over the course of the next year. In 2021, Georgia producers harvested more than 3.3 billion pounds of peanuts from 750,000 acres planted, accounting for approximately 52% of the peanuts produced in the U.S. in 2021.

“Peanuts are not a highly perishable crop and can be held up to a year in storage. In a perfect world, you would be able to harvest a crop and sell it quickly, but it takes time for industry to need the volume of peanuts harvested every year,” Kemerait said.

Stringent testing

Stringent aflatoxin testing is performed at harvest and throughout the production process to ensure that aflatoxins do not get into the final product

Peanuts designated for use as seed are sampled and sent to the Georgia Department of Agriculture’s Tifton Agricultural Seed Lab, where technicians test each sample for germination and check for aflatoxin. To be sold as state-certified seed in Georgia, seeds must be disease-free and demonstrate a minimum 75% germination rate, said Dee Dee Smith, a seed analyst at the lab. Testing for Georgia producers is funded by the state of Georgia. The lab also tests and certifies seed from Florida, Alabama and Texas, processing up to 10,000 seeds every six months.

“Whenever you find seed from Georgia, whether it is vegetables or grass or peanuts, there is a tag on that bag that documents all the information from our testing,” said Smith. “We are making sure that when a farmer goes out and buys 2,000 pounds of seed to go plant on their acreage, they know exactly what they are getting.”

Every crop of peanuts is tested at the buying point, including peanuts designated for use in food products that are sold to consumers by companies like Birdsong Peanuts, which has buying points around the Southeast and operates three shelling plants in Georgia.

“This is a pretty simple process. Our shelling plants don't do any further processing. All we do is take the peanuts out of the shell and we send out the peanuts as a still-raw product to our customers,” said Joshua Harper, a senior sales manager with Birdsong Peanuts. Birdsong sends samples of each crop of shelled peanuts to third-party labs for testing.

“We cannot ship out an edible product that does not meet aflatoxin specs,” Harper added.

On the shelf

About 75% of Georgia's peanuts are used to make peanut butter, and U.S. consumers eat about 700 million pounds (or 350,000 tons) of peanut butter per year — approximately 3 pounds per person annually. Seem like a lot? One acre of peanuts will make about 30,000 peanut butter sandwiches.

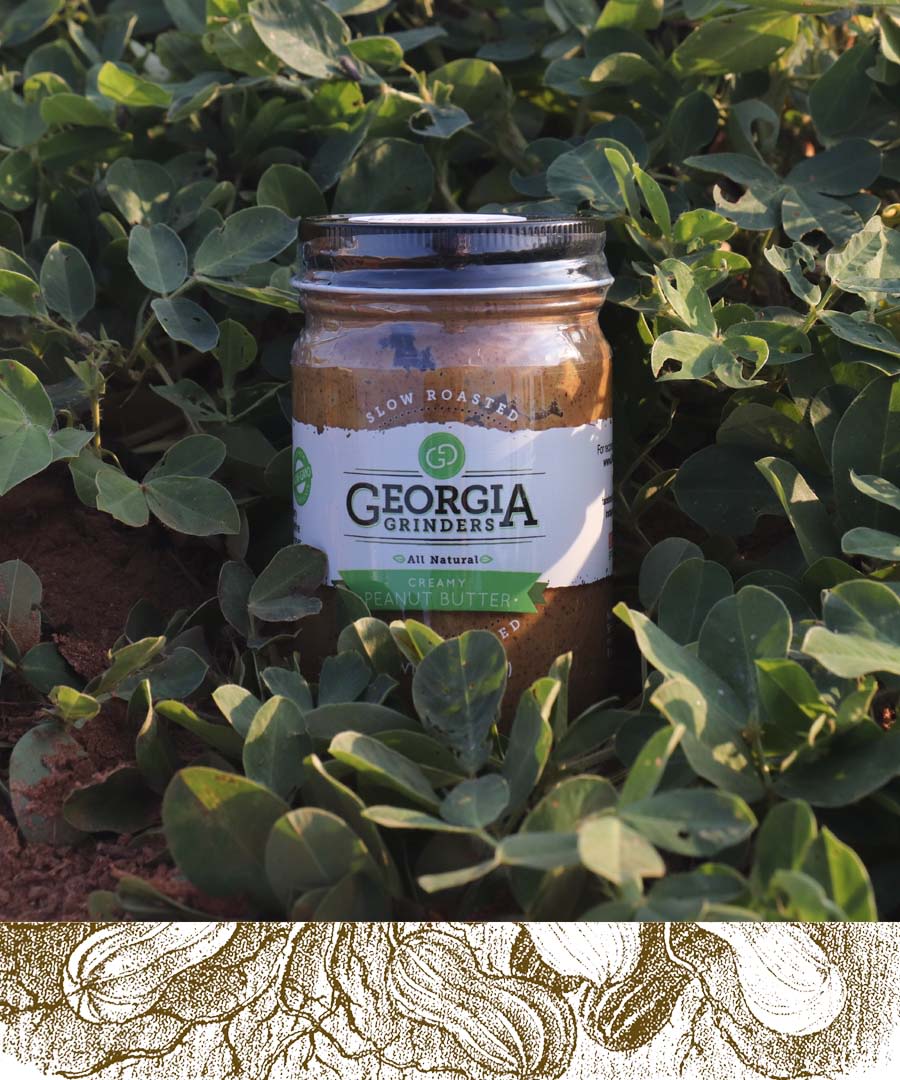

Jaime Hinsdale Foster, a 1999 CAES graduate, is the owner and founder of Georgia Grinders premium nut butters, which was launched in 2012. While they produce about 40 tons of peanut butter per year, Foster is grateful that the company is small enough to maintain its connections to the growers who produce the peanuts they use, specifically in their organic peanut butter.

“It fits in with our philosophy of ‘From Ground to Grind,’” said Foster, who created the company to bring clean, nutrient-dense products to market in tribute to her grandfather, Jim Hinsdale, on whose recipe the company’s original almond butter was based. “We looked in our backyard and decided to capitalize on the peanuts and pecans that are produced in our state. All our peanuts are sourced from Georgia, which is important to us for a whole host of reasons, from keeping it local and honoring our ties to the state to supporting Georgia producers and reducing our carbon footprint. Just like our peanut butter, we want to keep it simple.”

The company’s pecan butter was a grand prize winner of the 2017 Flavor of Georgia food product contest, an annual CAES event with competitors in a dozen categories from across the state. In 2021, Georgia Grinders introduced its USDA Certified Organic creamy and crunchy peanut butters to market through collaboration with Georgia Organics and the Georgia Organic Peanut Association.

“After all, Georgia is the peanut capital of the world and Georgia Grinders is headquartered just outside of Atlanta in Chamblee, Georgia. It is important to us that we support our state's agricultural industry and, being a CAES alumnus, my educational roots too,” Foster said.

Editor's note: This is part three of a three-part series exploring peanut production in Georgia. To read part one, visit “Breeding the best peanut.” To read part two, visit “Planting to picking, good peanuts start from the ground up.”

Did you enjoy this story?

Check out recent issues of the Almanac for more great stories like this one.

News media may republish this story. A text version and photos are available for download.