FIELD TO JAR: PART 2

Planting to picking, good peanuts start from the ground up

Variety selection, disease management and harvest timing are critical to Georgia’s peanut farmers

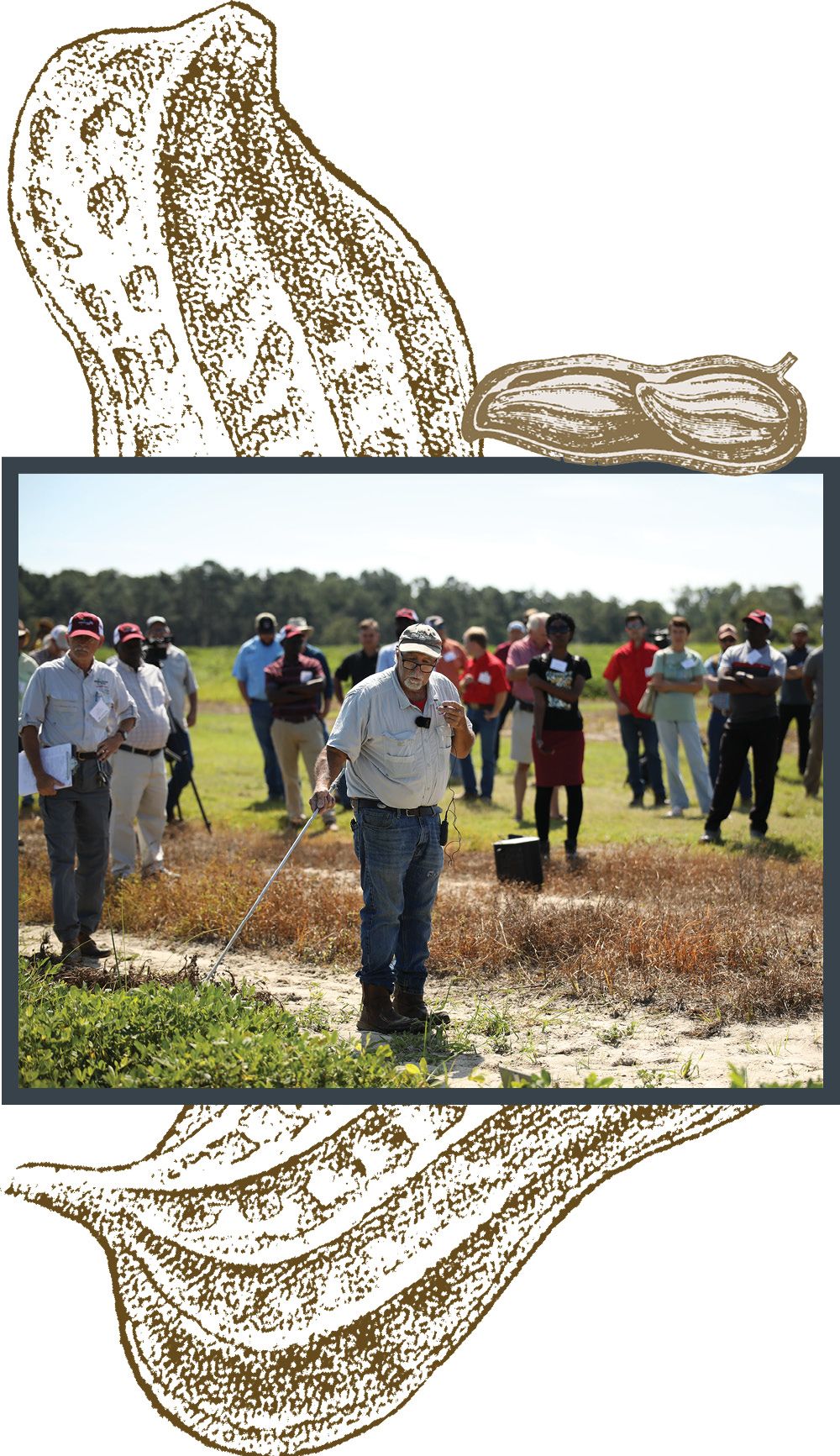

UGA peanut plant pathologist Bob Kemerait speaks to the crowd during the 2022 Georgia Peanut Tour.

UGA peanut plant pathologist Bob Kemerait speaks to the crowd during the 2022 Georgia Peanut Tour.

From year to year, many row crop producers rotate the crops they plant to reduce pest and disease pressure and to benefit the land, often alternating peanuts with cotton and corn. Peanuts in particular are considered an important cash crop for many farmers.

“We recommend that producers only grow peanuts in the same field one out of every three years,” said University of Georgia peanut plant pathologist Bob Kemerait. “Some farmers tell me they grow cotton and corn because they can, but they grow peanuts to make a living.”

Developed by UGA peanut breeders, the majority of peanuts planted in Georgia are runner variety peanuts, also the predominant market type grown in the U.S. The state’s most-planted variety — ‘Georgia-06G’ — was released in 2006 by Georgia Seed Development Professor in Peanut Breeding and Genetics and longtime UGA peanut breeder Bill Branch. ‘Georgia-06G’ has gained popularity for its kernel size, high yields and strong resistance to tomato spotted wilt virus, or TSWV, one of the most damaging diseases for peanut producers.

Variety selection is one of the most important decisions in peanut production, according to Peanut Grower magazine and UGA Cooperative Extension experts who work directly with the state’s growers. But once a grower chooses a variety, the work of growing a crop begins. With an Extension presence in every county, Agriculture and Natural Resources agents counsel growers on every aspect of production.

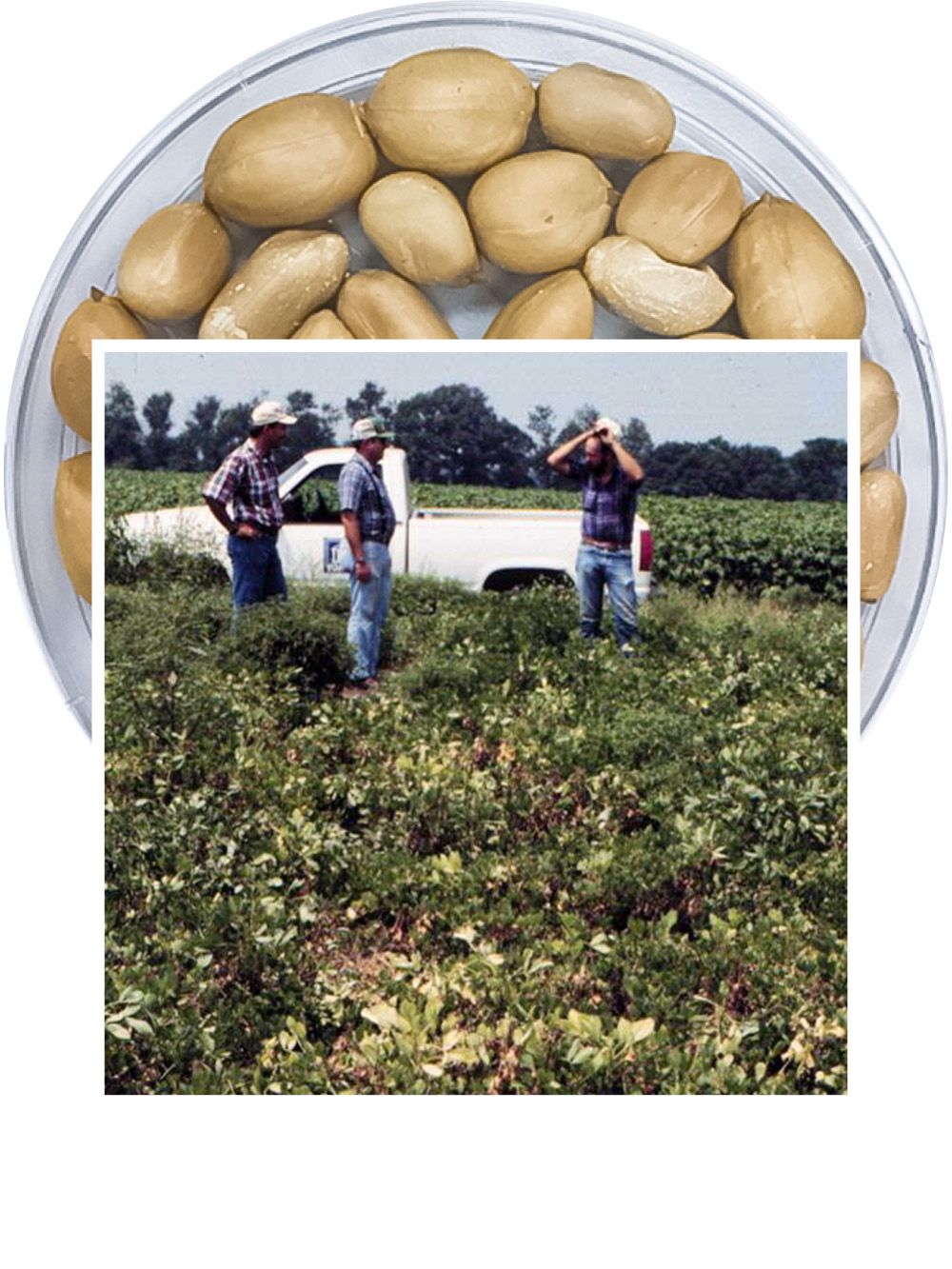

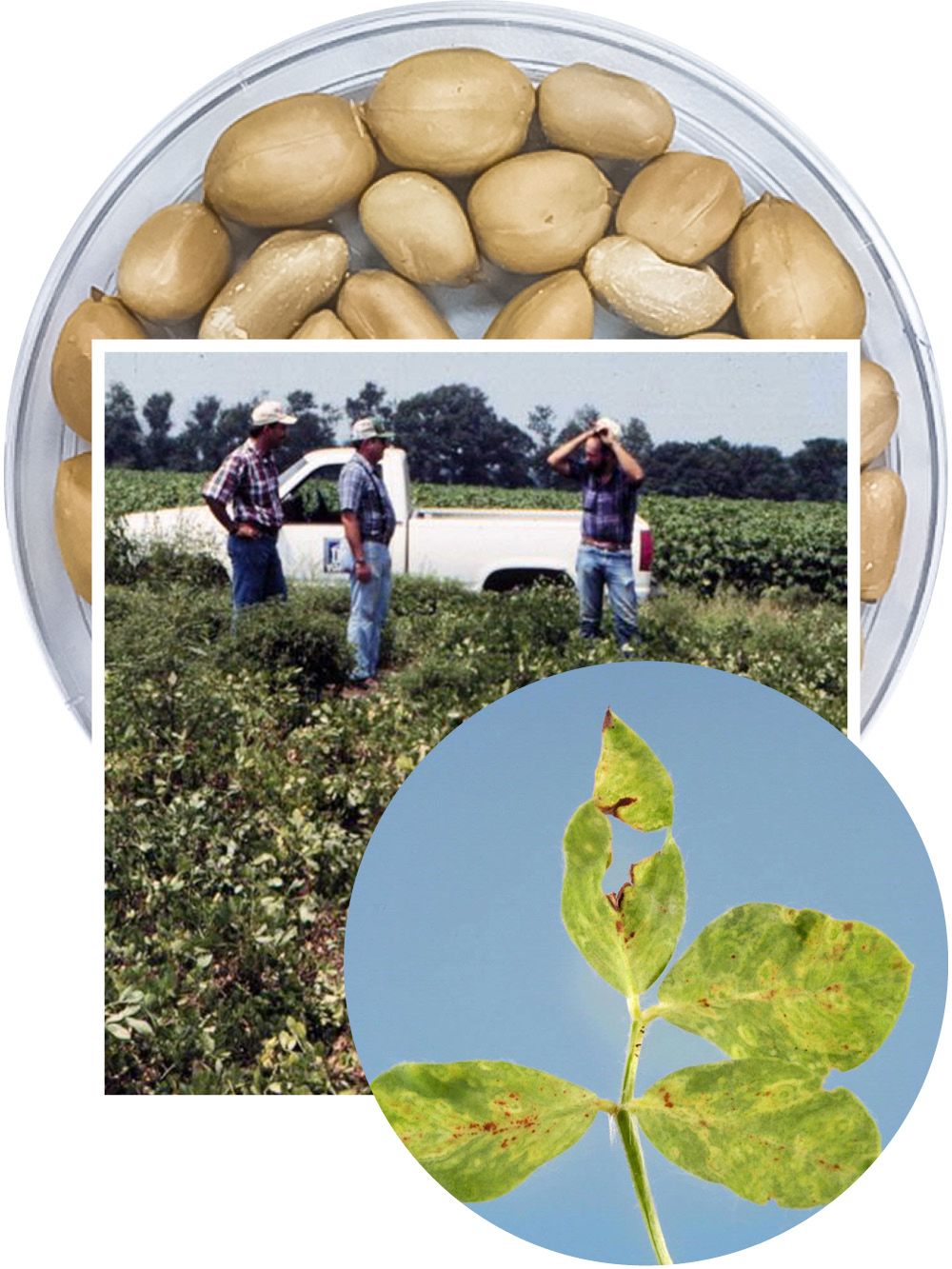

Georgia-06G peanuts are a runner-type peanut variety developed by UGA’s Coastal Plain Experiment Station in Tifton, Georgia, and released in 2006. It has high yield, large seed size, an excellent shelling rate, and good resistance to the spotted wilt disease caused by tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV).

Georgia-06G peanuts are a runner-type peanut variety developed by UGA’s Coastal Plain Experiment Station in Tifton, Georgia, and released in 2006. It has high yield, large seed size, an excellent shelling rate, and good resistance to the spotted wilt disease caused by tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV).

Peanut producers stand in a field infected with tomato spotted wilt virus in 2008. (Photo by Steve L. Brown, UGA, Bugwood.org)

Peanut producers stand in a field infected with tomato spotted wilt virus in 2008. (Photo by Steve L. Brown, UGA, Bugwood.org)

Tomato spotted wilt virus is spread by thrips and causes yellowing, mottling and crinkling of the leaves. (Photo by Jeffrey W. Lotz, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Bugwood.org)

Tomato spotted wilt virus is spread by thrips and causes yellowing, mottling and crinkling of the leaves. (Photo by Jeffrey W. Lotz, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Bugwood.org)

Getting seeds in the ground

Peanut production and research occupies much of Justin Hand's time, particularly at planting and harvest times.

“Getting the soil nutrients right, getting the soil pH right, getting them planted and getting them up takes a lot of work,” said Hand, Agriculture and Natural Resources agent for Tift County.

Once peanut stands are established, plant pathology specialists like Kemerait are instrumental in helping farmers minimize losses to diseases in those fields.

“Managing the diseases that affect the peanut crops in Georgia and around the world are critical because there is no sustainable peanut farming without managing disease,” said Kemerait. “From white mold disease to tomato spotted wilt virus, we’ve got at least five diseases in Georgia alone that can be devastating to peanut, and the reason they're not devastating in a grower’s field is because of the management and the research that has gone into this crop.”

A coordinated effort

Because the causal agent of some plant diseases, like tomato spotted wilt virus, are vectored by insect pests such as thrips, plant pathologists work closely with ANR agents, breeders, entomologists, agronomists and growers to develop new control strategies. These strategies range from bred resistance and production practices to integrated pest management and the use of agricultural chemicals.

“The growers are having to manage these diseases every single year, in every single field. Every peanut farmer in every field has to have a management practice, or they may not be able to grow peanuts profitably,” Kemerait said.

“Everything we do is integrated. We do not do this as a single discipline — it's not just plant pathology, it’s not just entomology, it's not just agronomy. We have worked together to come up with a ’systems approach’ to make producers more profitable.”

Kemerait has long been a part of the team in the continued development of Peanut Rx, a web-based tool that was created by peanut scientists at UGA and in neighboring states to help producers make critical crop decisions. The tool provides guidance based on a number of risk factors including variety planted, inputs, row pattern, tillage, plant population, crop rotation, disease pressure, irrigation and planting date.

“The beautiful fields of peanuts you have seen are beautiful because the farmers have gone the extra length to make it happen and they get their information from the research and Extension from UGA and our sister institutions around the country,” Kemerait said. “We are grateful for funding for the research that comes from many different sources, to include the Georgia Peanut Commission, the National Peanut Board, partners in the agricultural industry and other sources as well.”

Professor Albert K. Culbreath points out foliar fungal diseases and tomato spotted wilt virus during the 2022 Georgia Peanut Tour.

Professor Albert K. Culbreath points out foliar fungal diseases and tomato spotted wilt virus during the 2022 Georgia Peanut Tour.

Field science

Over the past two decades, advancements in agricultural technology have helped growers improve peanut production practices, from the use of global position systems (GPS) during harvest to precision planting and technology-assisted irrigation.

Simer Virk, pictured at right, is an assistant professor in the Department of Crop and Soil Sciences and precision agriculture specialist with UGA Extension.

“A lot of this technology is being developed and implemented in the Midwest where the prevalent crops are corn and soybeans, and we're finding ways to better integrate those technologies into peanut production,” said Virk as he demonstrated a variety of technologies used in peanut production, including planters that can be programmed to control seeding rate and planting depth, sprayers programmed to apply varying rates of pesticides and autonomous drones that can collect high-resolution data for in-season crop management and even spot-apply pesticides. All of the technologies are connected to sensors and portable networks designed to keep producers on top of every aspect of production until harvest.

At the end of the growing season, UGA Extension is there to help growers determine crop maturity and optimal harvesting dates.

“The farmer works all year and makes a lot of decisions from planting all the way through to harvest to make the determination on when to dig,” said Tim Brenneman, professor of peanut and pecan disease management in the CAES Department of Plant Pathology and a member of the UGA Peanut Team. “With peanut harvest you have one shot, so you have to make sure you make that shot count because it can have a big influence on your yield.”

For popular variety ‘Georgia-06G’, the average maturity period is 140 days from planting. Maturity checks begin at about 120 days to see whether the crop is maturing early and to determine the best harvest dates.

“We check maturity for the farmers, and we are out here helping them set up diggers, watching them pick and going through different grades on each field to see if we are accurate in our maturity checking and digging points,” said Hand, adding that weather conditions such as severe storms can impact harvest date.

Precision agriculture specialist and professor Simer Virk demonstrates a variety of technologies used in peanut production.

Precision agriculture specialist and professor Simer Virk demonstrates a variety of technologies used in peanut production.

Simer Virk demonstrates an autonomous drone that can collect high-resolution data for in-season crop management and even spot-apply pesticides.

Simer Virk demonstrates an autonomous drone that can collect high-resolution data for in-season crop management and even spot-apply pesticides.

“With peanut harvest you have one shot, so you have to make sure you make that shot count because it can have a big influence on your yield.”

UGA developed a peanut maturity scale and a method of maturity testing for runner peanuts that involves pressure washing a sample of peanuts from a field to remove the outer hull of the shell.

UGA developed a peanut maturity scale and a method of maturity testing for runner peanuts that involves pressure washing a sample of peanuts from a field to remove the outer hull of the shell.

Precision picking

When large-scale growers are raising a peanut crop across 600 to 700 acres, maturity is likely to vary from field to field, so it is a process that is repeated multiple times in a harvest season to pinpoint the optimum maturity for each field, Hand said.

Proper timing of harvest is critical to a grower’s bottom line, as picking too early can impact grade and yield by weight if the peanuts do not fully mature. However, picking too late can be disastrous.

“The more mature the peanut, usually the better the grade, but once they get overmature, they will start to sprout underground or start to rot, or when you dig them, the pegs can break leaving the pods in the soil,” Hand said. “Those peanuts may be heavy and full, but if they have come off the vine because they are too mature, you’ve lost them.”

To help pinpoint peak maturity, UGA developed a peanut maturity scale and a method of maturity testing for runner peanuts that involves pressure washing a sample of peanuts from a field to remove the outer hull of the shell.

While still wet, these samples are compared to the peanut maturity scale, which uses a color range in stages from white through yellow to brown through black to gauge maturity across a given sample. Using the scale, agents can give farmers an estimate of when they will get the best harvest.

Editor's note: This is part two of a three-part series exploring peanut production in Georgia. To read part one, visit “Breeding the best peanut.” To read part three, visit “UGA researchers work to develop innovative solutions to aflatoxin contamination in peanuts.”

Did you enjoy this story?

Check out recent issues of the Almanac for more great stories like this one.

News media may republish this story. A text version and photos are available for download.