(Watercolor by Ada Astacio)

(Watercolor by Ada Astacio)

FIELD TO PANCAKES: PART 1

Georgia, the Blueberry State?

Georgia is well-known as the Peach State, but since 1949 plant breeders at the University of Georgia have been on a blue streak, bringing more than 50 blueberry varieties to market.

Georgia has long been referred to as the Peach State, yet the fleshy fruit that adorns souvenirs and license plates isn’t counted among the state’s top 10 commodities. Blueberries join that list.

UGA blueberry breeder Scott NeSmith, professor emeritus in the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences (CAES) Department of Horticulture, has released more than 40 varieties during his career at the university.

“The UGA blueberry breeding program has been a key to the success of launching a significant commercial blueberry industry in Georgia in the 1980s and helping sustain it for four decades,” NeSmith said. “Dr. Tom Brightwell is the true pioneer of blueberry breeding and helped launch the blueberry industry in Georgia.”

Brightwell began his work at UGA in the 1940s, continuing until his retirement in the early 1970s. His focus was developing blueberry varieties from plants collected in the wild.

“It was some years after his retirement before the industry actually took hold, but they did so by using the varieties that he developed,” NeSmith said.

NeSmith said Georgia’s flourishing blueberry industry – and his own breeding career – were built on the foundation Brightwell laid.

“Our industry is now at a stage where we can produce, given cooperative weather, well in excess of 150 million pounds per year in a good year,” NeSmith said. “That’s a long way from the 5 to 10 million pounds of the 1990s.”

(Watercolor by Ada Astacio)

(Watercolor by Ada Astacio)

Breeding a better blueberry

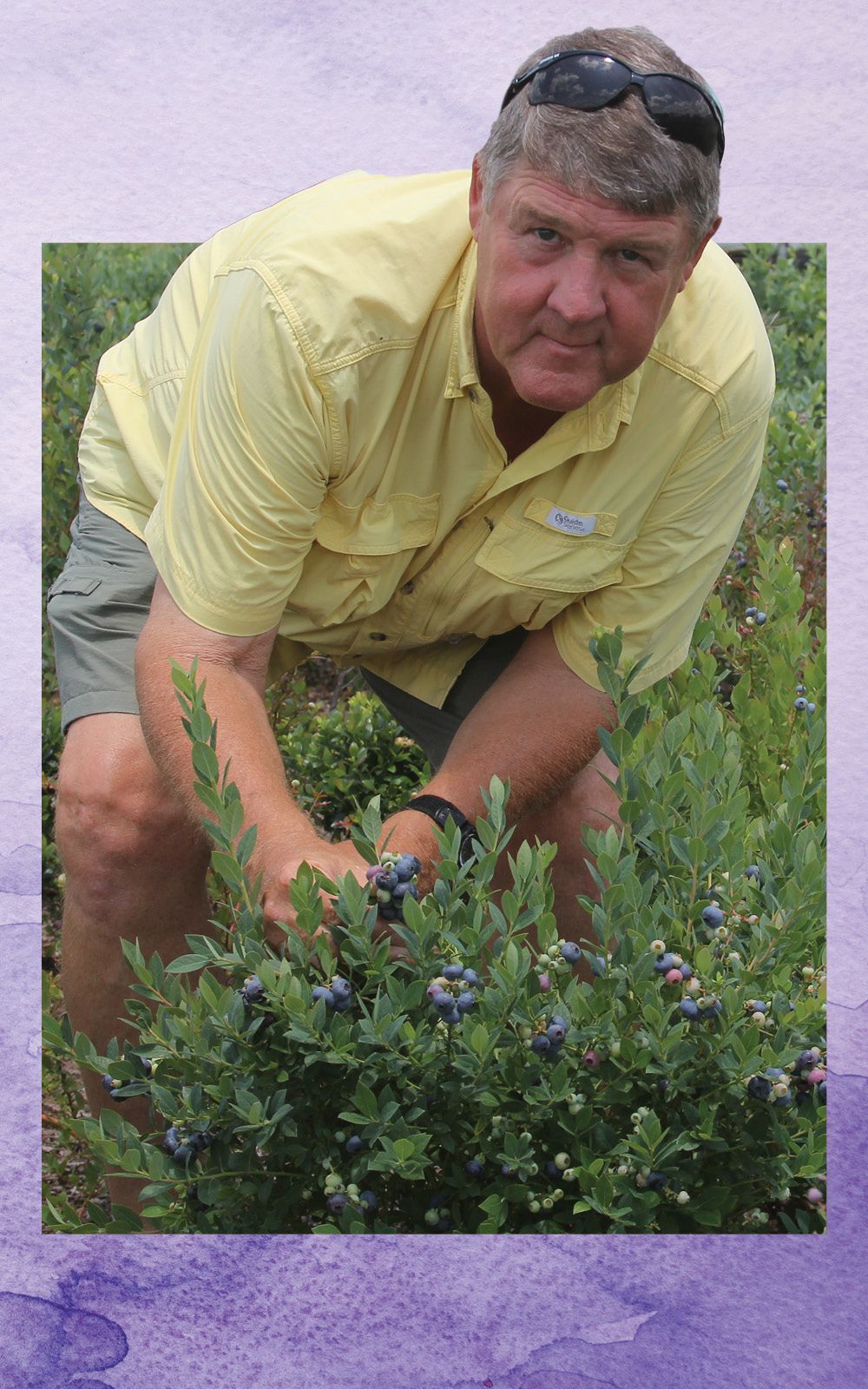

“One of the major factors we search for in breeding are plants that grow and produce in our varied environment,” NeSmith said. “Rabbiteye varieties were what gave us our start, and these were the focus of the breeding program for the first 30 to 40 years. This species is well adapted to the heat of the Southeast, and they are some of the easiest plants to grow.”

Rabbiteye bushes typically have a smaller fruit size and ripen later in the blueberry season – often well into June. This led researchers to turn their interest to another species, the southern highbush. While desirable for their larger fruit, earlier ripening and overall better fruit quality, southern highbush varieties weren’t as easy to grow in Georgia’s climate and production systems.

“My effort in breeding was to help expand the southern highbush industry by developing more hardy, easy-growing plants that our growers could grow,” NeSmith said. “I also worked to improve rabbiteye fruit size, quality and earliness. Today, we continue to look for well-adapted plants in our breeding program, but we have also put a major emphasis on fruit quality.”

Customers are becoming much more selective in their purchase of fruits and berries, NeSmith said, paying particular attention to flavor, texture and storage properties.

“Our breeding program seeks to enhance these attributes in our berries for consumers,” NeSmith said.

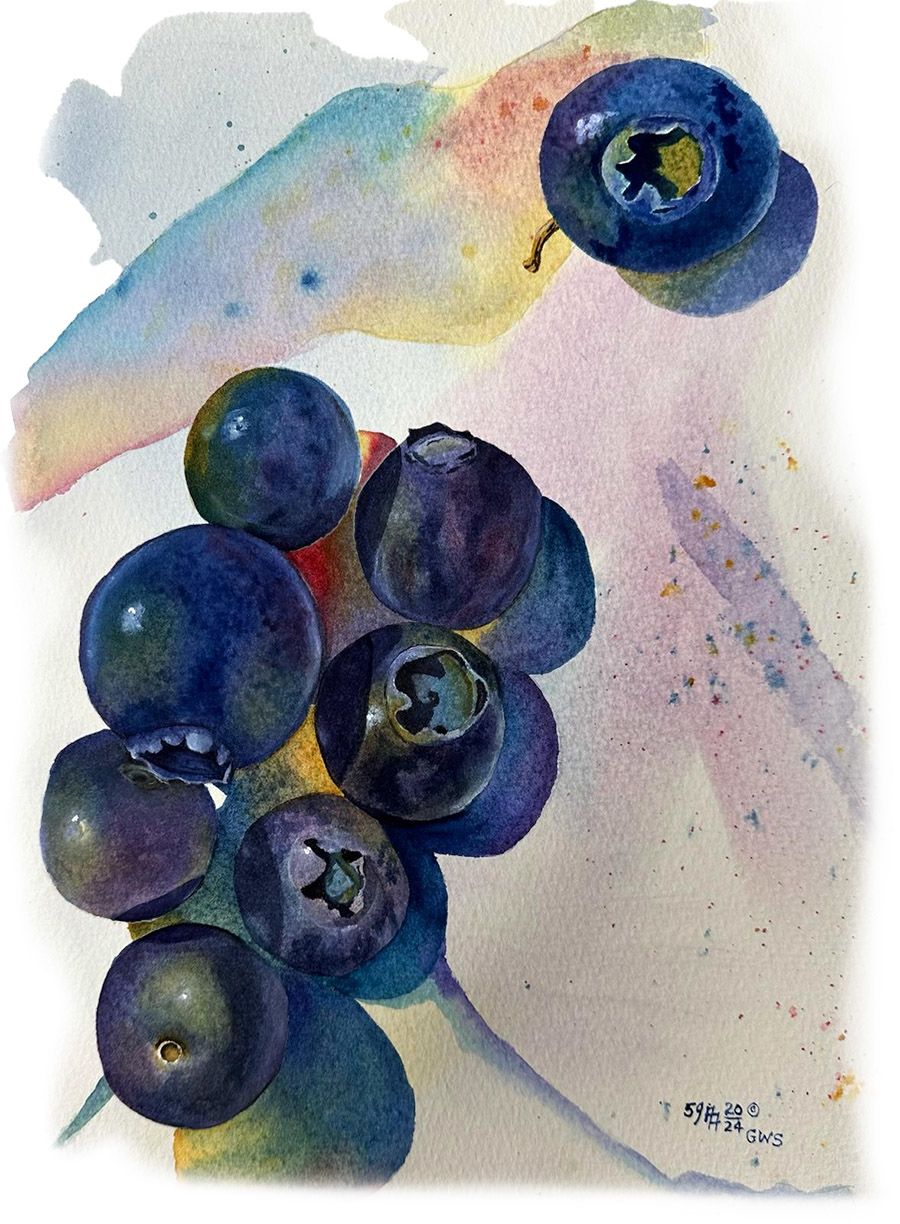

UGA Professor Scott NeSmith examines a blueberry breeding trial on the Westbrook Farm on the UGA Griffin campus in 2018. (Photo by Sharon Cruse)

UGA Professor Scott NeSmith examines a blueberry breeding trial on the Westbrook Farm on the UGA Griffin campus in 2018. (Photo by Sharon Cruse)

Close-up of a rabbiteye blueberry (Photo by Jerry A. Payne, USDA Agricultural Research Service, Bugwood.org)

Close-up of a rabbiteye blueberry (Photo by Jerry A. Payne, USDA Agricultural Research Service, Bugwood.org)

UGA-bred blueberries are licensed in nearly a dozen states, including Washington, California, Hawaii and Florida.

UGA blueberries can be found on farms across North America, from Canada to Mexico.

Scott NeSmith visits growers in Peru to establish test sites for UGA blueberry germplasm and examine diverse blueberry varieties currently grown in the country.

Scott NeSmith visits growers in Peru to establish test sites for UGA blueberry germplasm and examine diverse blueberry varieties currently grown in the country.

UGA-bred blueberries from Peru feed the Georgia market during November, December and January. Several Latin American countries have found UGA varieties suitable for local climatic conditions.

UGA has produced blueberries that thrive from Europe's temperate zones to Morocco's tropical climate, allowing for staggered production and exports. “The beauty is that when we license blueberries in China or Japan or even in southern Africa and Europe, we aren’t competing with Georgia growers,” said Brent Marable, assistant director of UGA's Innovation Gateway.

Blueberries grow in the Western Cape of South Africa.

Blueberries grow in the Western Cape of South Africa.

Two southern highbush blueberry varieties bred by NeSmith in research plots on the UGA Griffin campus are grown in territories in Europe and several countries in Africa, including Namibia and Zimbabwe.

For more than a decade, NeSmith has worked with Mitsunori Ozeki, owner of Ozeki Blueberry Nursery in Japan, a longtime licensee of UGA-patented blueberry varieties. According to Ozeki, Japanese growers like the giant berry size of the UGA varietal 'Titan' pictured above.

Going global

A modern consideration for keeping customers happy is creating year-round availability of blueberries.

“Blueberries are in such demand from consumers worldwide due to their many health benefits and great eating quality,” NeSmith said. “In Georgia, and in the U.S. as a whole, we can only produce berries for a limited time each year. For example, here in Georgia our season typically runs April through June, then we are through.”

The global demand for blueberries throughout the year has led to several international partnerships with the UGA blueberry breeding program, with partners in Europe, Africa, New Zealand, Japan and South America — including a unique breeding program in Peru.

“In order to keep blueberries in consumer’s hands year-round, countries like Peru have stepped up to find ways to produce berries in other times of the year. For Peru, it is from August to December, so this helps keep fresh blueberries on our grocery shelves all the time,” NeSmith said.

The partnership with Peru began more than a decade ago, when the CEO of a Peruvian grower reached out to the breeding program to see about the possibility of getting UGA blueberry genetics to trial in the South American country. After an initial visit, NeSmith’s team sent a few selections to Peru to trial in the desert-like coastal conditions. While Georgia’s blueberries experience a season of cold weather and dormancy, Peruvian blueberry plants would not receive this period of rest due to a more tropical climate.

“Our breeding effort at UGA primarily focused on plants that exhibit superior performance under such conditions,” NeSmith said. “Only certain genetics will succeed under this type of environment. To find such varieties, we had to expose the genetics to their environment.”

As expected, many failed the test. Yet, to researchers’ surprise, several performed exceptionally well.

“It took more than eight years to bring the first variety to market,” NeSmith said. “It truly was a partnership effort.”

These collaborations with farmers outside the U.S. not only provide consumers with blueberries year-round, they also bring valuable revenue back to the UGA blueberry breeding program.

“Regardless of where they are growing, UGA-bred blueberries feed the Georgia market during our season and, when they are licensed to be grown in other parts of the world, we can have blueberries to consume in other months as well,” said Brent Marable, assistant director for plant licensing with UGA's Innovation Gateway. “Consumers benefit from the availability of the fruit almost year-round, and royalty revenue generated from those blueberries goes back to the university to fund more research into breeding the next blueberries.”

Securing a sustainable future

While researchers are focused on a steadily available, grocery-ready product for consumers, they are also keeping a close eye on the challenges that can prevent blueberries from making the journey from the bush to the produce section.

“One of the biggest challenges for our industry going forward is the availability of labor,” NeSmith said. “The future of blueberries requires that varieties be created that can be harvested with machines instead of people.”

UGA’s blueberry program has been working on the issue for years and has produced some varieties that can work in new, mechanical systems. Researchers are continuing to breed and improve plants to produce fruit that is both acceptable to consumers and can survive machine harvesting, handling and packaging. All while keeping producers in mind.

“We need to continue to develop plants that grow well for farmers, hopefully with fewer inputs, such as fertilizers and water, so that their profit margins can be sustained,” NeSmith said.

Leading this charge will be Ye “Juliet” Chu, who will succeed NeSmith in leading UGA’s blueberry breeding program.

“Dr. NeSmith has retained over 1,000 selections of rabbiteye and southern highbush blueberries at our research farm, which allows our partners and growers to continue selecting for new varieties,” said Chu, assistant professor of horticulture and faculty in the CAES Institute of Plant Breeding, Genetics and Genomics with an emphasis on blueberry breeding. “Looking forward, we intend to broaden the genetic base of our breeding program through interspecific hybridization and will engage genetic tools to accelerate the breeding effort.”

Editor's note: This is part one of a three-part series exploring blueberry production in Georgia. Check out the whole series and subscribe to CAES Updates to receive future stories in your inbox.