FIELD TO PANCAKES: PART 2

Blueberry fields forever

University of Georgia develops techniques, tools and best practices for sustainable blueberry production amid climate change.

Zilfina Rubio Ames

Zilfina Rubio Ames

For Zilfina Rubio Ames, blueberry research begins after the plant is bred and in the ground.

An assistant professor of horticulture in the University of Georgia’s College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences and a small-fruit specialist with UGA Cooperative Extension, Rubio Ames endeavors to better understand blueberry plant physiology and how it can be manipulated to increase production efficiency.

“We are in a moment in time where we are concerned about how much fertilizer we are providing to the production system and how that affects the sustainability of the system, not only in terms of the environment but also how fertilizer affects the sustainability of the industry in economic terms,” Rubio Ames said.

Over the past decade, fertilizer prices have risen substantially, making it increasingly expensive for growers to keep producing the state’s primary specialty fruit crop. Researchers are looking at methods to improve the blueberry production system, making it more sustainable without reducing yield or impacting fruit quality.

Rubio Ames is focused on creating a balanced nutrient plan for blueberry producers around the state. While growers know a lack of nitrogen, for example, can cause damage to yield, excessive nitrogen fertilization will both increase expense and likely create a plant with increased vegetative growth and less fruit.

(AI image generated by Adobe Firefly)

(AI image generated by Adobe Firefly)

“This is not only for nitrogen, but for phosphorus, potassium, calcium, boron and all these fertilizers the plant needs — those nutrients are important,” Rubio Ames said. “My main area of research is looking at fertilization practices and how reducing or increasing those fertilization practices alters plant physiology, in this case blueberry physiology.”

Rubio Ames also focuses on improving management practices, including pruning techniques and the use of plant growth regulators, to protect crops from variable climate conditions — especially Georgia’s spring freezes.

“Last year we had a detrimental freeze that wiped out almost 50% of the crop,” Rubio Ames said. “How can we find tools that could help us overcome these biotic and abiotic challenges that the blueberry production system has in the state of Georgia?”

Implementing proper pruning techniques, while far from a new practice, is vitally important to improved blueberry production.

“If we increase nitrogen fertilization we increase vegetative growth, and then we have an unbalanced plant that has more leaves than flowers,” Rubio Ames said. “Pruning is a technique that allows us to manage the plant, shaping and training the plant the way you want so it is able to harvest all the light possible.”

Rubio Ames is managing several projects involving pruning, from timing — as pruning can invigorate growth — and how pruning impacts the physiology of the blueberry plant and influences production.

“We usually prune in July, in the summer, right after the harvest is finished. But what if we don’t prune at that time? What if we wait until wintertime to prune? Will that be beneficial?” she asks.

Rubio Ames’ research has one overarching goal: to make production more efficient and economically viable for growers, which leads to more blueberries for consumers to enjoy.

Properly pruning blueberry plants can make a big impact on yield.

Upon planting a blueberry bush, UGA horticulturists recommend removing low, twiggy growth entirely and tipping the remaining shoots to remove all the flower buds. About 1/3 to 1/2 of the plant top should be removed in this process. Mulch 3 to 6 inches deep with pine needles or pine bark after planting.

For more information on blueberry care including recommendations for pruning established plants, see UGA Extension Circular 946, "Home Garden Blueberries."

Pursuing a precarious balance

One factor in the blueberry’s success in Georgia is the climate; blueberries require cold temperatures during growth, which is why many varieties don’t succeed in fully tropical climates.

“We have enough chill hours to produce a crop,” said Pam Knox, an agricultural climatologist and director of the UGA Weather Network. “Here in Georgia, we’re near the southern limit of where blueberries can grow successfully in the U.S. They will always require a certain amount of cold weather over the winter months.”

Chill hours are a way of keeping track of the accumulation of cold weather that affects a crop. Growers count every hour where the temperature reaches 45 degrees Fahrenheit or below. While some methods of tracking chill hours involve stopping a count if the temperature dips below 32 degrees, or even “resetting the clock” if a frost hits, Knox said the simplest way is to track all hours below 45 degrees.

“You can buy blueberry varieties that require an average of 1,000 chill hours or only require 500 chill hours,’” Knox said. “Once the plant gets to that magic number, it has gone through enough cold weather that, when it comes out of dormancy when we have a warm spell, it’s ready to bloom.”

In addition to temperature — from accumulating sufficient chill hours to the risk of late frost events that can kill spring blooms — availability of water is another key concern for Georgia’s blueberry growers. While many commercial producers irrigate, Knox said supplementary irrigation required during dry years increases costs for growers and can lead to issues with disease.

“For a good blueberry year, it’s a combination of having the chill hours come gradually and then not having a late frost; plus having sufficient water so that growers don’t have to do a lot of irrigation but not so much that they can’t access the fields,” Knox said.

It’s a precarious balance.

Producing blueberries in a changing climate

While Knox helps blueberry producers each growing season, she’s also looking years into the future for the long-term viability of blueberries in Georgia and the Southeast.

“We know that it is getting warmer, and we know that winter is the season that’s getting warmer the fastest,” she said. “That means fewer chill hours. Farmers can adjust by planting earlier-blooming varieties, but they still have the possibility of getting a frost that could affect the crop.”

If plants require fewer chill hours and bloom earlier to accommodate a warming climate, they are more vulnerable to a frost event that could destroy a producer’s entire crop for the year.

“Farmers can look to diversify their crops, so they have different chill hour requirements on different fields,” Knox said. “Even if a frost does get some of them, it likely won’t get them all.”

Researchers have also developed and released sprays that can be used to protect crops during a frost event. Some protect existing crops by insulating plants while others delay dormancy break, according to Knox, but all come with a high price tag.

“To protect blueberries, growers must place overhead irrigation, running water over the blueberries, to form ice over the top of the plants and fruit — and that is expensive. Not everyone can do that,” Rubio Ames said. “Researchers and industry are very interested in looking at plant growth regulators to hopefully delay blooming so flowers avoid the spring freezes.”

Like animals, plants produce hormones, natural compounds that trigger different biochemical reactions. Plant growth regulators, Rubio Ames added, are the result of synthesizing those hormones in the laboratory instead of in the plant.

“The blueberry industry in Georgia is being challenged by high production costs and labor issues,” Rubio Ames added. “Even though there are a lot of challenges out there, there are still a lot of blueberries to produce.”

Researchers hope this multipronged approach will lead to increased production across the state and reduce production costs.

“Blueberries are a highly sought-after commodity,” Knox said. “I don’t think we’re going to stop growing them anytime soon. Blueberries have enough varieties that we should be able to get by, but it’s going to be a bit riskier than in the past — but so will everything else because of the changes in extreme weather.”

Learn more about UGA blueberry research and outreach work at extension.uga.edu.

Editor's note: This is part two of a three-part series exploring blueberry production in Georgia. Check out the whole series and subscribe to CAES Updates to receive future stories in your inbox.

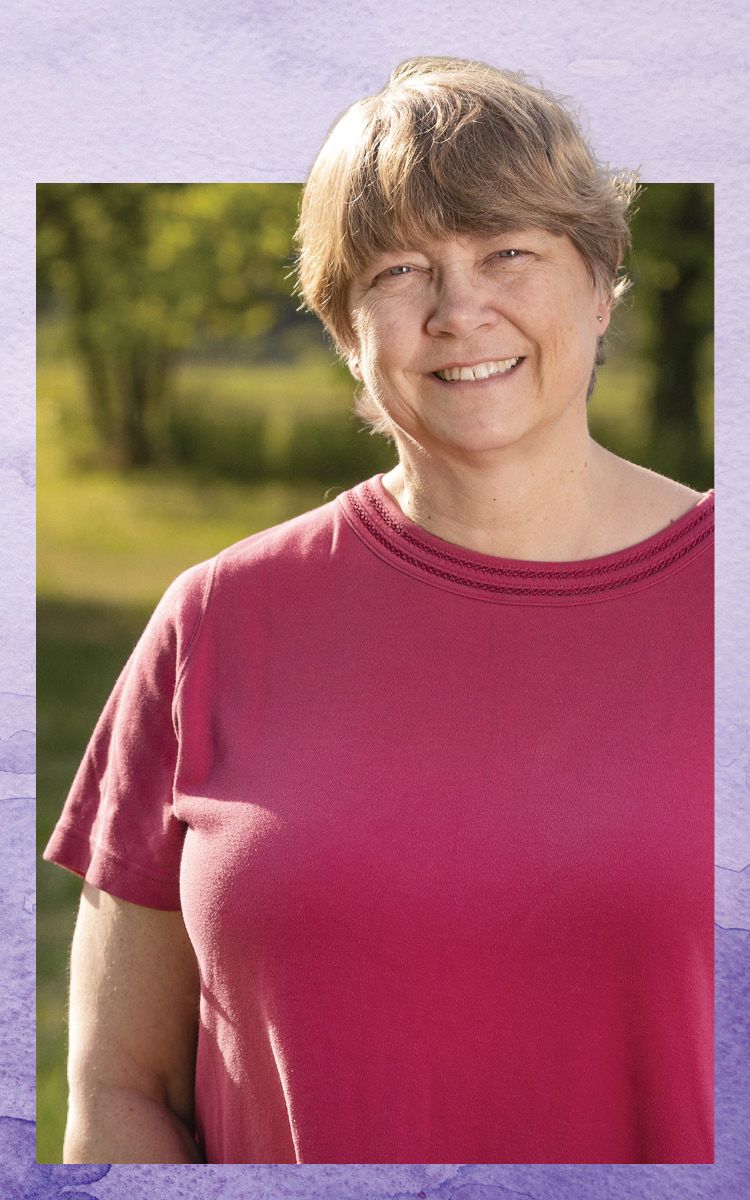

Pam Knox

Pam Knox

(Composite AI image generated by Adobe Firefly)

(Composite AI image generated by Adobe Firefly)