Weathering Change

How can we achieve agricultural resilience in a changing climate?

Agriculture is dependent on nature.

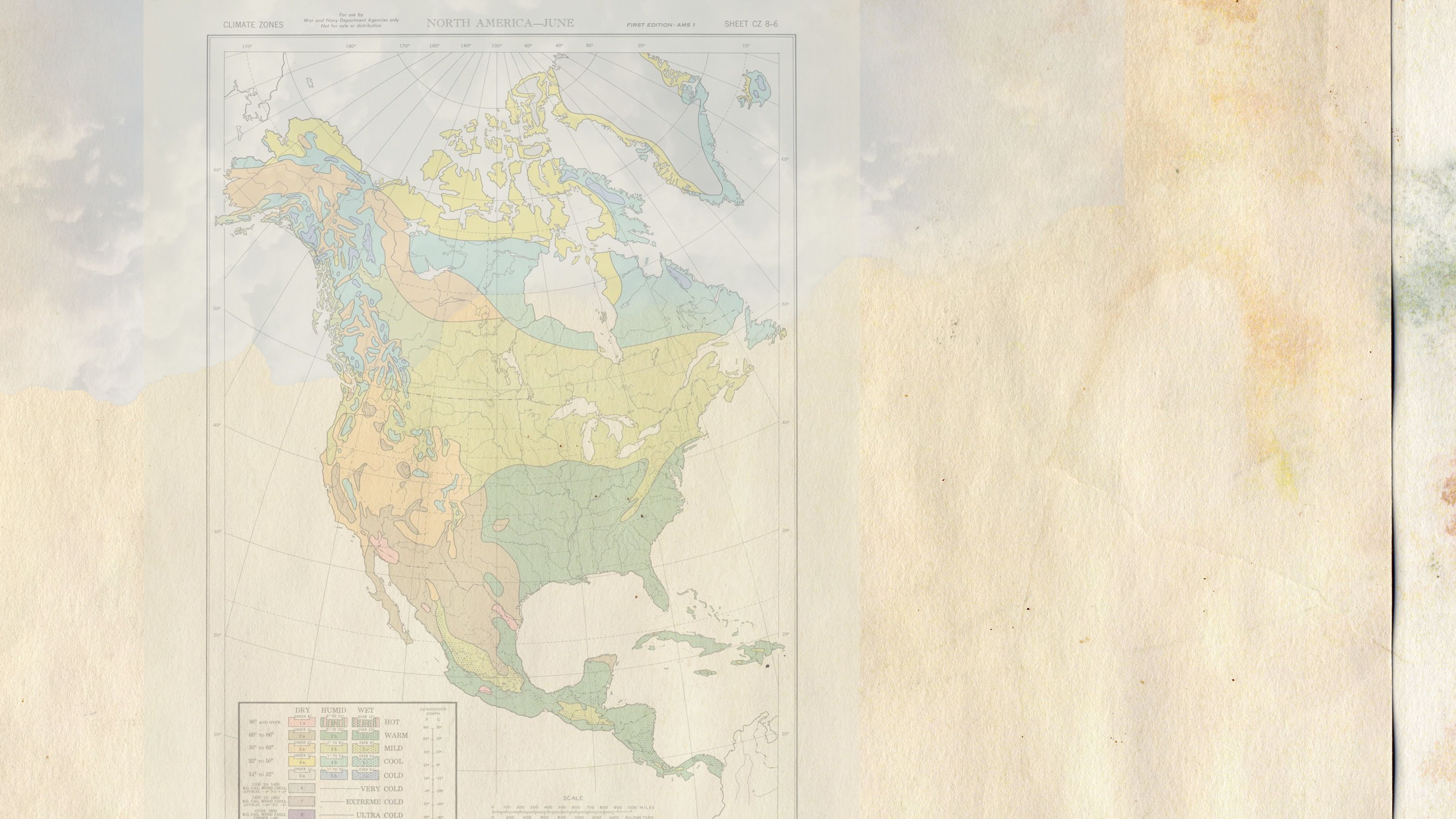

Even seemingly minor temperature variations have a significant impact on the precise mechanics of plants, animals and insects. As average temperatures have warmed by 3 degrees over the past century, the question remains — how will we adapt our agricultural practices to ensure that all people continue to have access to food, fiber and fuel now and in the future?

This is where the University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences comes in. After a record-breaking year in 2024 with more than $258.8 million dollars spent on research and development, CAES scientists continue to galvanize the college as a global leader in agricultural and environmental research.

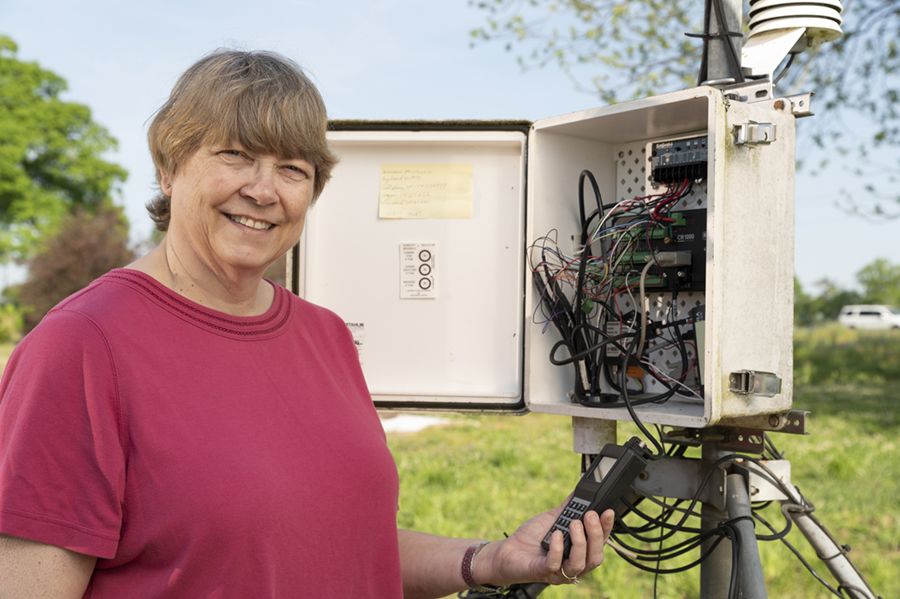

Analyzing a screen of data from weather stations across the state, UGA Weather Network Director Pam Knox explained that increasingly extreme weather patterns are indicators that the water cycle is being amplified. Knox is an agricultural climatologist at UGA, providing outreach and education on climate and its effects on crops and livestock in the Southeastern U.S. She also gathers weather and climate data and provides analyses to university scientists throughout the region.

Agricultural climatologist Pam Knox checks a weather station in Watkinsville, Georgia. (Photo by Dennis McDaniel)

Agricultural climatologist Pam Knox checks a weather station in Watkinsville, Georgia. (Photo by Dennis McDaniel)

“Here, and around the world, as temperatures warm, we’re going to see an exacerbated cycle of drought and flooding,” said Knox.

For more than 30 years, the Georgia Automated Environmental Monitoring Network has been collecting weather information throughout the state for agricultural and environmental applications. Knox pointed out that as temperatures increase, it causes more evapotranspiration from the soil and evaporation from lakes and streams, which bring surface water levels down. Conversely, as temperatures increase, so does the relative humidity. As water evaporates from the surface, it accumulates in the clouds. When conditions are just right, those clouds can dump large quantities of water in a short time.

Higher relative humidity leads to another problem. Excessive water vapor in the air holds more energy, which prevents temperatures from cooling off, especially at night. From livestock to plants, it’s the warmer nighttime temperatures that have the greatest impact on agriculture, Knox said.

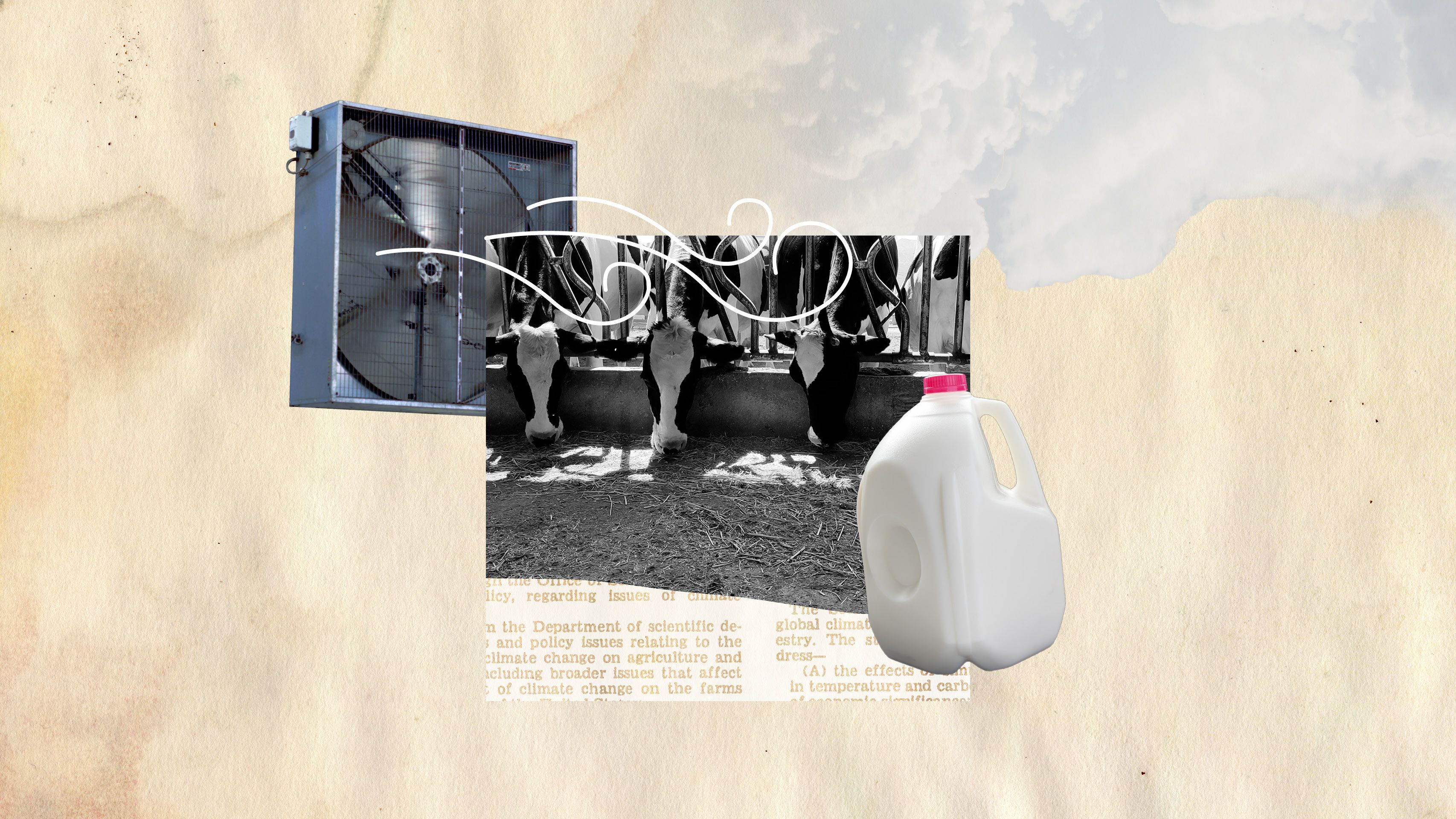

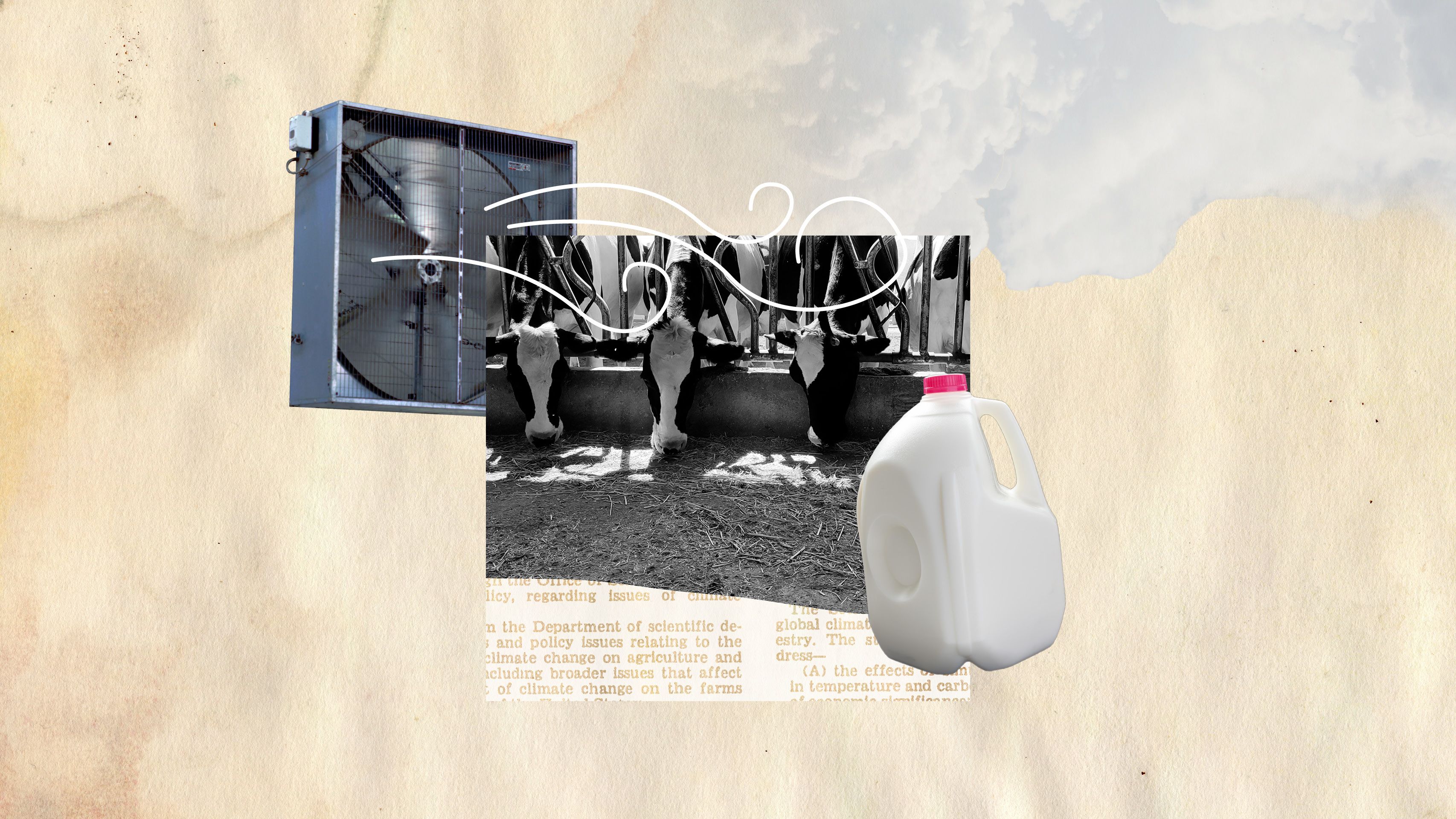

Livestock have a harder time cooling off to recuperate from the heat of the day, which leads to decreases in milk production and slower weight gain. And while farmers can install shade structures throughout fields and fans and misting sprinklers in barns to improve evaporative cooling, these methods only go so far, Knox explained.

“Warming trends in the Southeast aren’t going away, so it’s more likely our farmers will need to diversify their herds with breeds that are better adapted to warmer climates going forward.”

Diversification is a concept echoed by Tim Coolong, Department of Horticulture professor and UGA Cooperative Extension vegetable specialist.

Farmers are increasingly aware of their loss potential when they have all their eggs in one basket. “If there’s one thing I recommend most to farmers, it is to diversify crops to mitigate the direct risks of climate variability and the indirect impacts of market swings that often result from climate-related issues,” he said.

Coolong tells farmers to consider growing vegetables throughout the year, something called double or even triple cropping.

During Tim Coolong’s years as state vegetable specialist, his research focused on variety trials and developing irrigation and fertilization recommendations for farmers. (Photo by Dorothy Kozlowski)

During Tim Coolong’s years as state vegetable specialist, his research focused on variety trials and developing irrigation and fertilization recommendations for farmers. (Photo by Dorothy Kozlowski)

“If sweet potatoes in the summer are your bread and butter, and you by some chance lose that crop, you are prepared to plant a second crop for the fall to lean on,” he said. “We don’t have control of temperatures, and farmers can’t just pick up and move to avoid these issues, so we look at other solutions within the farm, such as growing more heat- or drought-tolerant crops and using precision agriculture tools to increase resilience in the face of variability.”

Breeding programs are critical to developing varieties that are better adapted to warmer temperatures and drought-like conditions.

CAES horticulturist Dario Chavez, who specializes in peach production and management, is working to breed a climate-adapted peach. Some of his current efforts involve improving and protecting peach genetics through work with the South Georgia Peach Breeding Program, a partnership with the University of Florida and the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Peach trees require a certain number of chill hours — the number of hours where the temperature is between 32 and 45 degrees Fahrenheit — while the plant is dormant during the winter, Chavez explained. If the number of chill hours is not met, there can be issues with plants coming out of dormancy, including problems with bloom, fruit development and lowered fruit yield.

Dario Chavez, associate professor of horticulture on the UGA Griffin campus, shows off the drip irrigation system in the Dempsey Research Farm peach orchard used to study irrigation and fertilization management for young peach trees. (Photo by Ashley Biles)

Dario Chavez, associate professor of horticulture on the UGA Griffin campus, shows off the drip irrigation system in the Dempsey Research Farm peach orchard used to study irrigation and fertilization management for young peach trees. (Photo by Ashley Biles)

Through the breeding program’s diverse genetic inventory, breeders are developing varieties with adjusted chill hours without compromising the yield and quality of the fruit. “We’re interested in finding genetic material adapted to the current conditions in south Georgia and north Florida,” said Chavez.

As the climate changes, premature warm temperatures in late winter are increasingly causing fruiting trees and shrubs to bloom early. When followed by freezing temperatures, blooms are damaged, lowering yield and, in severe cases, completely killing the buds. This can have a devastating economic impact on Georgia’s fruit industries. CAES researchers are studying nanocellulose, which could potentially be sprayed over blooms to protect them from the cold.

Knox has estimated that for every 1-degree change in average temperature, the growing season increases by about one week. While that can benefit farmers, it also means an increasingly longer season for plant diseases, weeds and insect pests.

“Climate change is an interesting subject because the severe impact that we generally discuss at the scientific level plays out at a more subtle rate in the field,” said Ash Sial, associate professor of entomology at UGA.

“Growers may see slight changes from one year to the next, but when you zoom out and look at several years lined up, that’s when you start to see the larger impacts climate change has on agriculture.”

Sial, coordinator of UGA’s Integrated Pest Management Program, said working with insects provides a living example of the effects climate change is having at the ecosystem level. Warmer winters allow pest populations to survive and multiply earlier in the season, requiring farmers to spray pesticides more frequently, he said.

Historically, farms used to be more ecosystem-based and more diversified, but as the population drastically increased, smaller farms could no longer meet the growing demand for food. Monoculture began to dominate modern agriculture, which increased mechanization and pesticide use.

“Now, we’re learning that spraying our way through the season is not going to work,” said Sial. “Secondary pest problems arise when our natural enemies and beneficial insects are depleted.”

Farmers will need to use systems-based approaches, considering how everything on the farm is connected, which will help them become more proactive each year.

Ultimately, Knox said we’ll have to brace ourselves for more variability going forward. As a global leader in agricultural and environmental sciences, CAES will continue to address the issues facing agriculture and the environment through proactive, world-class research efforts.

News media may republish this story. A text version and art are available for download.

Did you enjoy this story?

Check out recent issues of the Almanac for more great stories like this one.