Research with Reach

UGA faculty excellence attracts international researchers across disciplines

Each year, hundreds of international researchers — from master’s degree students to academic faculty — apply to come to the University of Georgia to work in a wide range of academic fields.

In the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, dozens of international research scholars work with faculty on important research that furthers the CAES mission while benefiting visiting scholars and their home institutions.

“Our faculty get the benefit of working with experienced research scholars who are funded by their home governments or institutions to come here for several months up to a year. They are full members of the labs they work in and their goal is to be as productive as possible and to publish academic papers based on their work,” said Victoria McMaken, coordinator of international programs at CAES.

CAES is among the top colleges at UGA for the number of international research scholars hosted each year, said Robin Catmur-Smith, director of immigration services with the UGA Office of Global Engagement.

“We have people from all over the world who come to UGA to do research and teach. In a non-COVID year, we host about 900 international scholars and faculty each year,” Catmur-Smith said. “In addition, we have about 2,500 international students each year from more than 100 countries.”

CAES spoke to several international scholars and their faculty mentors about the work they are doing at UGA and the benefits to both the scholars and UGA. Spotlights of additional visiting scholars can be viewed on the Office of Global Engagement website.

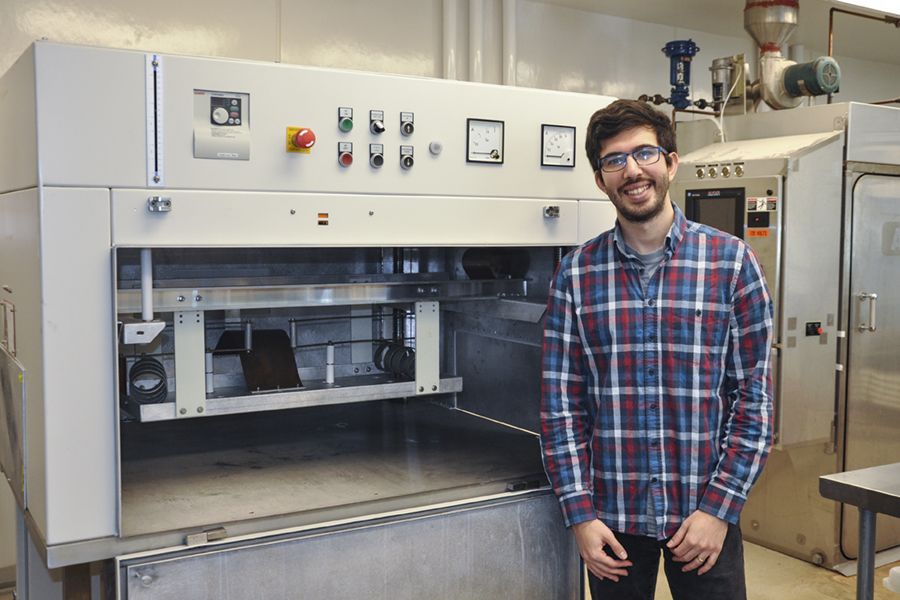

Ozan Altin

Home institution: Ankara University, Ankara, Turkey

Education: Doctoral student, Department of Food Engineering

Faculty sponsor: Fanbin Kong, professor in the Department of Food Science and Technology

Altin’s doctoral research focuses on the thawing process of frozen food products in parallel electrode radio frequency systems. His goal is to develop an innovative system design, determine the optimum processing conditions and learn the effects on drip loss and texture in frozen chicken breast meat.

At UGA, Altin works with Kong using mathematical computer modeling to compare three methods of radio frequency thawing technology on frozen chicken breast meat. In the lab, he prepares samples for radio frequency thawing using fiber-optic probes connected to a computer to monitor second-by-second temperatures during the process, collecting data on surface temperature distribution using thermal imaging cameras. He then validates the previously developed models based on the experimental data. The purpose of the study is to determine the optimum process condition based on the end quality of the chicken meat, comparing color, texture and drip loss using the technology at UGA compared to systems in Turkey.

“I change the parameters of the process to see how it affects temperature distribution and other factors so we can optimize the processing,” said Altin, who values the one-on-one interaction he has had with his UGA mentor. “Dr. Kong has provided very good advice for my doctoral thesis, and other faculty have been open to me using their laboratories and equipment.”

After completing his doctoral work, he hopes to continue designing innovative radio frequency systems for industrial applications.

“There are more opportunities here at UGA because the department is very developed and they have advanced equipment,” said Altin, who is supported by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey, a national agency.

Kong said the research contributions Altin has made are meaningful to his work to develop novel thawing technology for frozen food products, which can help improve food quality.

“Mentoring international scholars like Ozan helps enhance research efficiency and productivity. The international collaboration also helps promote the influence of our research and boost the impact of our lab at UGA and brings new opportunities for research and for our students,” said Kong.

Taketo Haginouchi

Home institution: Kagoshima University, Kagoshima, Japan

Education: Master’s degree candidate, meat science

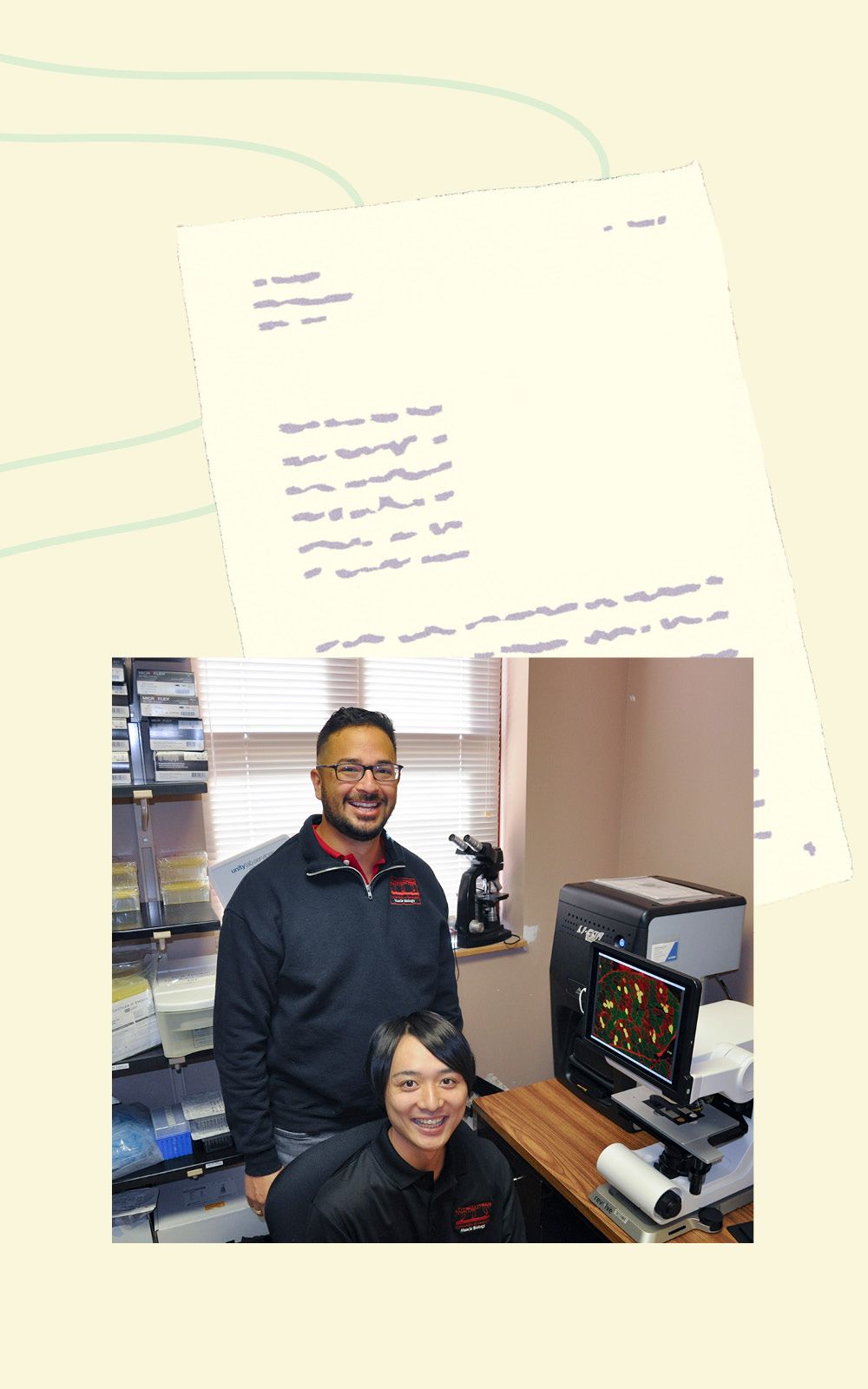

Faculty sponsor: John Michael Gonzalez, associate professor, Department of Animal and Dairy Science

As a master’s degree student at Kagoshima University, Haginouchi’s research focuses on fetal development in Wagyu cattle and how maternal nutrition influences offspring growth. Haginouchi’s graduate advisor at Kagoshima University is interested in metabolic imprinting, focusing on genetically “programming” cattle to grow more efficiently on grass. It takes about 10 tons of feed to raise one animal, and because Japan does not produce its own corn due to land scarcity, producers must import feed at a high cost.

Aimed toward improving the growth performance of grass-fed cattle, Haginouchi’s research is focused on influencing cattle at the fetus level to produce animals that are prone to grow more efficiently on a predominantly grass-fed system. Typically, grass-fed cattle are leaner than grain-fed cattle, which is not ideal considering the high fat content desired in Wagyu beef. Researchers are studying how the diet of the mother “programs” fetuses to be born with a higher fat content.

At UGA, Haginouchi is working with poultry to determine how a compound used to increase embryonic growth influences the development of muscle fibers in chicks, hoping to translate the science to Wagyu cattle research. Gonzalez’s recent research centers on manipulating embryonic muscle growth and looking at the effects of transportation on muscle fatigue in livestock.

“Japanese farms are very small and we have smaller production systems,” said Haginouchi, estimating that a large Wagyu farm in Japan may have 200 to 300 cattle, while a small producer may have only three to five animals. Wagyu cattle are raised in a very intensive, barn-based system versus larger, pasture-based cattle raising operations in the U.S. “Producers are interested in utilizing grazing systems for cattle in Japan.”

Having international researchers working at CAES benefits both the visiting scholar and CAES students, Gonzalez said.

“It is an easy way to get our students to become more worldly and in tune with different cultures. That has been a big focus of my program, trying to get students to understand that there’s a whole world out there full of possibilities and different cultures that we need to understand, accept and form friendships with.”

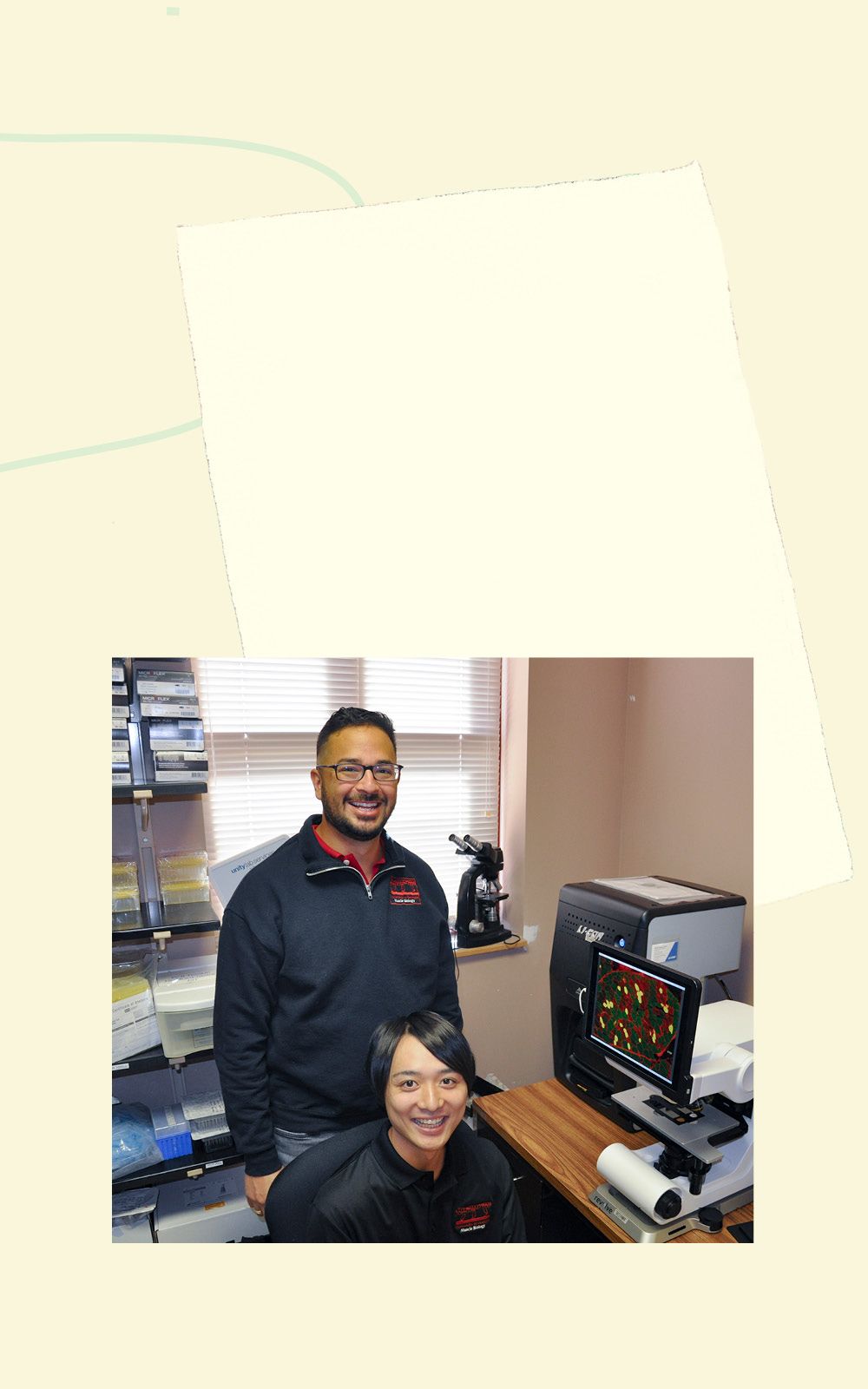

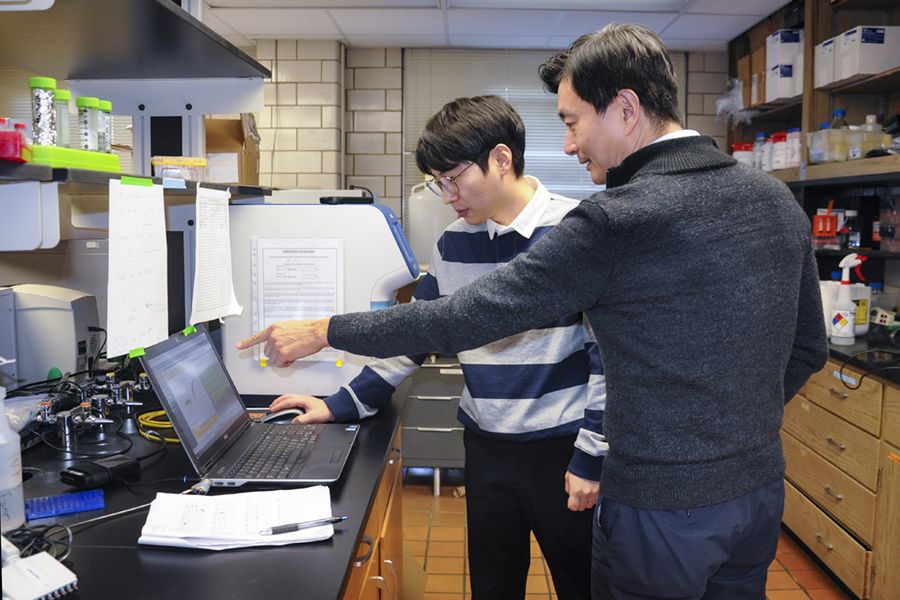

Jihwan Lee

Home institution: Chungbuk National University, Cheongju, South Korea

Education: Ph.D., poultry nutrition

Faculty sponsor: Woo Kyun Kim, professor, Department of Poultry Science

Lee is a specialist in monogastric animal nutrition with an interest in poultry nutrition. As a postdoctoral researcher in Kim’s lab, Lee is evaluating the function of amino acids in poultry challenged with coccidiosis and necrotic enteritis. Lee is also studying how gene expression in birds is related to poultry gut health.

Lee became interested in research opportunities at UGA after reading several journal publications authored by Kim, so he applied for the postdoctoral position open in Kim’s lab.

“Korea does not have enough research funding, so sometimes it is hard to analyze the various parameters needed in research. I was advised that if I came to the U.S., I would have access to the best research equipment and techniques,” he said.

Lee is one of many international students working in Kim’s and other poultry science labs, which helps expand their professional networks.

“Working with a diverse group of international students really benefits our students and early career researchers, as they can learn new things from international students and, after they graduate, they can continue to communicate and work together as friends and colleagues. Nowadays the world is small, so all the companies and universities working on poultry science have a lot of international collaboration, which is really important for progressing research,” Kim said.

“Our international students and researchers get experience in the U.S., and it is a benefit to researchers in the U.S. because each student or researcher brings new things from their own country. It is a win-win situation.”

Lee first pursued civil engineering before a documentary on swine and broiler chicken farms in Korea spurred his interest in the industry.

“Korea is making steady efforts to maximize animals’ performance to meet the growing demand for meat, and I want to help to improve how things are done in Korea,” he said.

Martha Sanchez-Tamayo

Home institution: Universidad de Valle, Cali, Colombia

Education: Ph.D., food engineering

Faculty sponsor: Faith Critzer, associate professor, Department of Food Science and Technology

Sanchez studies the antimicrobial properties of four essential oils (oregano, clove bud, coriander and cinnamon bark) against Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella and E. coli bacteria when incorporated into wax coatings for organic apples. After inoculating organic apples with the bacteria, Sanchez coats the apples with wax mixed with different concentrations and combinations of essential oils, testing the fruit over a defined storage period to determine the efficacy of the coatings.

“I have worked with antimicrobial coatings, specifically for mangoes, incorporating essential oils into coatings to see if they work against a specific fungus, Colletotrichum gloeosporioides,” said Sanchez, who continued her research at Washington State University, performing a six-month internship testing the efficacy of essential oils against Salmonella on mangoes.

The research has the potential to be used with other agricultural crops treated with edible wax, which is widely used to extend shelf life, improve appearance and reduce moisture loss in transport and retail display.

“Incorporating essential oils as natural antimicrobials is ideal for the organic market, as everything used in the production process has to be compliant with organic production,” Sanchez said. The project is supported by funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture’s Organic Agriculture Research and Extension Initiative. “This can be extendable to pretty much any product where wax coatings are used.”

After data collection, Sanchez and Critzer will perform sensory testing to determine if different formulations of essential oil-treated wax coatings impact the flavor or other sensory attributes of the fruit.

“Essential oils have been widely studied for their antimicrobial properties. One essential oil will have many chemical components, four or five of which are the primary antimicrobial compounds. We use a combination of essential oils based on their antimicrobial compounds to have specific antimicrobial characteristics, as some are more effective for fungi and others for bacteria. We are determining how to mix the best properties of all of them,” Sanchez said.

Sanchez chose her field of study to benefit people and producers.

“I was looking for something that can help people. I chose food engineering because of the close involvement with public health and food safety,” she added.

In addition to her research, Critzer said Sanchez has contributed to her lab by mentoring a master’s degree student.

“The questions are so numerous for graduate students when they are getting started, and sometimes the principal investigator isn’t there in the lab when you need them. It is nice to have someone who is well-trained and who understands the research to offer a calm and measured presence,” Critzer said. “Martha has been an excellent mentor, which is a lot of what we do as researchers in addition to the research metrics.”

Urtnasan "Uugii" Ganbaatar and UGA Professor Mohamed Mergoum attended the annual Norman E. Borlaug International Symposium, sponsored by the World Food Prize Foundation, in October 2022.

Urtnasan "Uugii" Ganbaatar and UGA Professor Mohamed Mergoum attended the annual Norman E. Borlaug International Symposium, sponsored by the World Food Prize Foundation, in October 2022.

Nurturing Knowledge

UGA geneticist mentors Borlaug Fellow to develop new wheat varieties for Mongolia

For Borlaug Fellow Urtnasan “Uugii” Ganbaatar, the opportunity to work with University of Georgia wheat breeder and geneticist Mohamed Mergoum is opening up a world of growth. With her colleagues at the Institute of Plant and Agricultural Sciences (IPAS), part of the Mongolian University of Life Sciences, Ganbaatar wants to implement the advanced breeding techniques used at UGA to improve her country’s dominant crop.

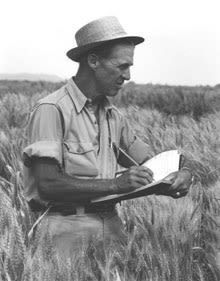

Ganbaatar’s 12-week research program at the UGA Griffin campus was funded by the Borlaug International Agricultural Science and Technology Fellowship Program, a highly competitive research and training program of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Foreign Agricultural Service for early to mid-career scientists, researchers and policymakers. The program, which brings fellows to a U.S. university, research center or government agency to collaborate with a mentor on a research project, honors Norman E. Borlaug, the American agronomist, humanitarian and Nobel laureate known as the father of the Green Revolution.

Norman Borlaug (Photo courtesy of the World Food Prize Foundation)

Norman Borlaug (Photo courtesy of the World Food Prize Foundation)

Plant breeding tech

A doctoral student in food biotechnology at the Mongolian University of Science and Technology, Ganbaatar has served as the head of the biochemical and technological laboratory at IPAS for eight years.

In her application for the Borlaug Fellowship, she proposed bringing samples of Mongolian wheat varieties for in-depth analysis using molecular technology, gel electrophoresis and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

Through the Borlaug Fellowship selection process, she was matched with UGA’s College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences and Mergoum, who is the Georgia Seed Development UGAF Professor in Wheat Breeding and Genetics in the Institute of Plant Breeding, Genetics and Genomics (IPBGG) and Department of Crop and Soil Sciences.

While molecular technologies including genomic selection (GS) and marker-assisted selection (MAS) are the standard in Mergoum’s lab, HPLC and gel electrophoresis are standard technologies still available in labs at UGA. He guided Ganbaatar's work using those technologies to identify genes associated with quality traits — including grain protein content and its component, high and low molecular weight glutenin — in 93 Mongolian wheat varieties. Ganbaatar’s institute owns equipment that can perform those analyses but lacks staff trained in its use.

About 90% of all agricultural production in Mongolia is devoted to wheat production, but without modern technologies, the wheat breeding process to develop and release new cultivars takes more than twice as long using traditional methods that cannot pinpoint desired traits. Ganbaatar will work with breeders at IPAS to try to adopt methods similar to those used in UGA’s small grains breeding program to hasten the release of new wheat cultivars.

“Wheat is our dominant crop and, when we are developing varieties, we have to spend a lot of time on the process because we can’t use molecular technologies due to lack of equipment, staff and laboratory area,” Ganbaatar said. Wheat varieties released by IPAS were developed over 28 years. UGA wheat breeders can develop and release a new variety within 10 to 12 years.

In addition to her work with Mergoum (left) on the UGA Griffin campus, Ganbaatar (right) visited UGA's Athens campus to meet faculty in the IPBGG and establish research connections.

In addition to her work with Mergoum (left) on the UGA Griffin campus, Ganbaatar (right) visited UGA's Athens campus to meet faculty in the IPBGG and establish research connections.

Mining for genetic gold

One of the main goals of the wheat breeding program in Mongolia is to produce improved varieties that will reduce the country’s dependence on imports of foreign wheat, which is currently mixed with Mongolian wheat for bread and flour production in the country.

During her fellowship, Ganbaatar worked with Mergoum to extract DNA from 93 cultivated and indigenous wheat varieties she brought with her from Mongolia to identify genes and traits that could be used to breed new cultivars using classical and genomic selection methods.

“Of the 93 samples I brought with me, 17 were developed at our institute and others are local, indigenous varieties no one has ever studied before,” she said. “If they have good qualities, we can use those for crossing with cultivated wheat to develop new varieties.”

Using advanced technologies to identify desired traits and associated genetic markers to develop improved germplasm — living genetic material such as seeds or tissues used in plant breeding — reduces the time it takes to develop new varieties and the guesswork associated with traditional plant breeding.

“Indigenous varieties are a gold mine for genes that control desirable traits because they have been grown for centuries and are adapted to the environment. They may not be the highest yielding, but they are fit, which means they have a balance of traits for productivity, quality and resistance to disease, pests or drought that cultivated varieties do not have,” Mergoum said. “Indigenous varieties may not perform as well in yield compared to modern varieties developed using modern tools and methods, but you can take desirable genes from those indigenous varieties and insert them into cultivated varieties.”

Ganbaatar took the training and knowledge she received in molecular technologies, gel electrophoresis and HPLC home with her to teach her colleagues, improving their research capabilities.

Continuing Borlaug’s legacy

Ganbaatar is the third Borlaug Fellow Mergoum has mentored at UGA. Previous Fellows were from Ukraine and Ethiopia.

“Borlaug believed that, as scientists, we have obligations to train people in developing countries so they can help themselves and sustain food production,” said Mergoum, adding that he had the privilege of working with Borlaug while serving as a scientist with the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research’s International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) in Mexico from 1995 until 1999.

“In science, you should take the barriers of universities and countries away — your goal is to improve production and help whoever needs help. At UGA we are a public university, and we want to have an impact, not only on the state or country, but worldwide,” Mergoum said.

Victoria McMaken, coordinator of international programs at CAES, explained that having international scholars like Ganbaatar working with UGA researchers is vital to developing long-term international collaborations with both individuals and institutions.

“It is our goal to be the No. 1 school of agriculture in the country and, to do that, we need to be well-known throughout the world. Every person who comes here to study extends that reach,” McMaken said.

In addition to working in Griffin with Mergoum, Ganbaatar visited UGA’s Athens campus to meet colleagues in the IPBGG to establish research connections and meet with other faculty, including Zenglu Li, Ali Missaoui and IPBGG director Wayne Parrott to gain insight into the most advanced technologies used in genetics and genomics, including genetic modifications.

The Borlaug Fellow program covers travel for mentors to visit mentee institutions after the U.S. fellowship is complete to follow up on the research initiated during the program and for knowledge exchange. Ganbaatar and Mergoum will also have the chance to jointly publish academic papers on their research.

“It will be good for Dr. Mergoum to come to my country to see our research conditions and to give good advice to improve our breeding program,” said Ganbaatar, who anticipates completing her doctorate in fall 2023. “I have learned so much from my mentor, U.S. Department of Agriculture staff and my labmates. I have increased my understanding of molecular biology, and what I have learned here will help improve the quality of wheat for seed and flour production in Mongolia.”

Did you enjoy this story?

Check out recent issues of the Almanac for more great stories like this one.