Red Dirt

Diplomacy

UGA plant pathologist Bob Kemerait shares his Fulbright experience in the Philippines, working to improve crop management and empower farmers at home and across the globe

Bob Kemerait's office overflows with books and mementos that reflect his global perspective and work as a UGA Extension specialist.

Bob Kemerait's office overflows with books and mementos that reflect his global perspective and work as a UGA Extension specialist.

Editor’s note

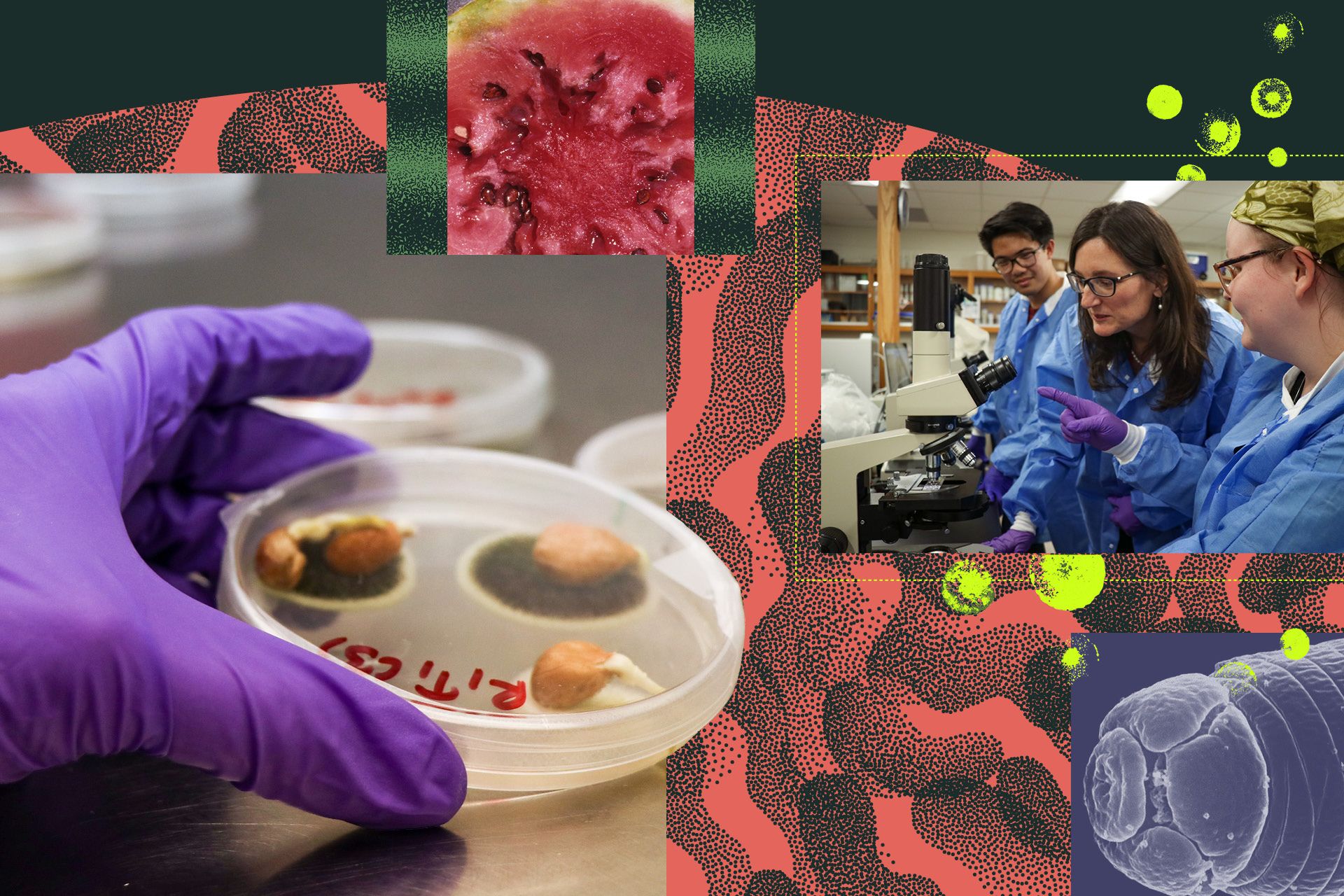

As a University of Georgia Cooperative Extension specialist in the UGA College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, Bob Kemerait is well known for his devotion to the agricultural community of Georgia. He is also known for his international work with colleagues and small-scale farmers around the world. Recently, Kemerait took a team from UGA Extension to the Philippines, where he serves as a Fulbright specialist and works with the faculty at Mariano Marcos State University and farmers in the northern Philippines to improve disease management and other production practices. Kemerait generously agreed to document his work in the following first-person essay.

With the sun setting over the distant mountain range and the South China Sea behind us, we listened as a Filipino farmer explained how the symptoms developed quickly, now scorching the foliage of his melon crop. Surrounded by his fish pond teeming with tilapia, mango trees laden with golden fruit, and small fields planted with onions and melons, this should have been a bucolic moment for my colleagues from UGA Extension. Instead, the gravity of the situation kept the mood somber for Ted McAvoy, Alton “Stormy” Sparks, Mark Abney, Jeremy Kichler and Ty Torrance, who were in the Philippines for the first time.

Addressing our UGA team, Walter Valdez and other colleagues from Bataan Peninsula State University, and provincial agricultural officers, the farmer asked what could be done to protect his crop now; he already applied a fungicide with little effect. Here on the Bataan peninsula, where 82 years ago Filipino and American soldiers fought the Japanese in a life-or-death struggle, today’s battle was against a foe that threatened this farmer’s livelihood.

Philippine downy mildew is a potentially devastating corn disease in the region. (Photo by Bob Kemerait/Bugwood.org)

Philippine downy mildew is a potentially devastating corn disease in the region. (Photo by Bob Kemerait/Bugwood.org)

As he knelt low among the diseased plants, Torrance called to us, “It’s downy mildew; I have rarely seen worse. At this stage, there is nothing that can be done; the crop will be a loss.”

I had to agree. The melons were six weeks away from harvest; in another week, the plants would be burnt and brittle. Though the farmer had done his best to protect the crop, the fungicide that he applied was not effective against this particular pathogen (Pseudoperonospora cubensis). Sadly, this was not the first time the disease affected this field; downy mildew went undiagnosed in cucumbers the previous year. Kichler noted, “It was discouraging. This grower in the Philippines needed information, the kind of information that our growers in Georgia have come to expect from us in UGA Extension.”

As a professor in the Department of Plant Pathology at UGA, I was deeply honored to be among those selected to participate in the Fulbright Specialist Program, which was established in 2001 by the Department of State’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs. According to its website, the Fulbright Specialist Program “pairs highly qualified U.S. academics and professionals with host institutions abroad to share expertise, strengthen linkages, hone their skills, gain international experience and learn about other cultures while building capacity at their overseas institution.” This program has been ongoing in the Philippines for 10 years.

I met Shirley Castañeda Agrupis, herself a Fulbright visiting researcher at Kansas State University in 2011, during previous visits to the Mariano Marcos State University (MMSU) campus. As president of MMSU, Agrupis believed that my experience in plant disease management would complement expertise within her faculty. UGA and MMSU established a memorandum of understanding that would make my presence even more appropriate. In cooperation with Mee Jay Domingo, director of external linkages and partnerships at MMSU, and through the World Learning Organization, which facilitates the Fulbright program, I was scheduled to travel to the Philippines in April 2020. However my Fulbright program was disrupted within days of my departure by the coronavirus.

After waiting more than three years, I was warmly welcomed to the MMSU campus in September 2023. I was assigned three objectives.

The first objective was to conduct research on plant disease and pest management of peanut, garlic, shallots and mung bean in five municipalities within Ilocos Norte: Piddig, Bacarra, Pasuquin, Vintar and Sarrat.

The second objective was to present lectures to undergraduate and graduate students related to pest management for these same crops, with an emphasis on the impact of climate and climate change on crop production in the region. During my stay I had daylong visits with the students in the College of Agriculture, Food and Sustainable Development on the Batac and Dingras campuses and with graduate students on the Laoag City campus.

My third objective was to train farmers and agricultural officers to identify and control diseases and pests in important crops. I was also tasked with helping them to better understand opportunities for Extension publications.

With the sun setting over the distant mountain range and the South China Sea behind us, we listened as a Filipino farmer explained how the symptoms developed quickly, now scorching the foliage of his melon crop. Surrounded by his fish pond teeming with tilapia, mango trees laden with golden fruit, and small fields planted with onions and melons, this should have been a bucolic moment for my colleagues from UGA Extension. Instead, the gravity of the situation kept the mood somber for Ted McAvoy, Alton “Stormy” Sparks, Mark Abney, Jeremy Kichler and Ty Torrance, who were in the Philippines for the first time.

Addressing our UGA team, Walter Valdez and other colleagues from Bataan Peninsula State University, and provincial agricultural officers, the farmer asked what could be done to protect his crop now; he already applied a fungicide with little effect. Here on the Bataan peninsula, where 82 years ago Filipino and American soldiers fought the Japanese in a life-or-death struggle, today’s battle was against a foe that threatened this farmer’s livelihood.

As he knelt low among the diseased plants, Torrance called to us, “It’s downy mildew; I have rarely seen worse. At this stage, there is nothing that can be done; the crop will be a loss.”

I had to agree. The melons were six weeks away from harvest; in another week, the plants would be burnt and brittle. Though the farmer had done his best to protect the crop, the fungicide that he applied was not effective against this particular pathogen (Pseudoperonospora cubensis). Sadly, this was not the first time the disease affected this field; downy mildew went undiagnosed in cucumbers the previous year. Kichler noted, “It was discouraging. This grower in the Philippines needed information, the kind of information that our growers in Georgia have come to expect from us in UGA Extension.”

As a professor in the Department of Plant Pathology at UGA, I was deeply honored to be among those selected to participate in the Fulbright Specialist Program, which was established in 2001 by the Department of State’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs. According to its website, the Fulbright Specialist Program “pairs highly qualified U.S. academics and professionals with host institutions abroad to share expertise, strengthen linkages, hone their skills, gain international experience and learn about other cultures while building capacity at their overseas institution.” This program has been ongoing in the Philippines for 10 years.

I met Shirley Castañeda Agrupis, herself a Fulbright visiting researcher at Kansas State University in 2011, during previous visits to the Mariano Marcos State University (MMSU) campus. As president of MMSU, Agrupis believed that my experience in plant disease management would complement expertise within her faculty. UGA and MMSU established a memorandum of understanding that would make my presence even more appropriate. In cooperation with Mee Jay Domingo, director of external linkages and partnerships at MMSU, and through the World Learning Organization, which facilitates the Fulbright program, I was scheduled to travel to the Philippines in April 2020. However my Fulbright program was disrupted within days of my departure by the coronavirus.

After waiting more than three years, I was warmly welcomed to the MMSU campus in September 2023. I was assigned three objectives.

The first objective was to conduct research on plant disease and pest management of peanut, garlic, shallots and mung bean in five municipalities within Ilocos Norte: Piddig, Bacarra, Pasuquin, Vintar and Sarrat.

The second objective was to present lectures to undergraduate and graduate students related to pest management for these same crops, with an emphasis on the impact of climate and climate change on crop production in the region. During my stay I had daylong visits with the students in the College of Agriculture, Food and Sustainable Development on the Batac and Dingras campuses and with graduate students on the Laoag City campus.

My third objective was to train farmers and agricultural officers to identify and control diseases and pests in important crops. I was also tasked with helping them to better understand opportunities for Extension publications.

My Fulbright program focused on the improved production of high-value crops grown during the dry season, however my September arrival meant I was there during the wet season. Much of my first week and a half was characterized by torrential rains from a lingering typhoon that wandered just off the northern coast of Luzon. The weather was perfect for the rice, but not for a thorough assessment of the crops for which I was summoned. For this reason, I returned to MMSU and Ilocos Norte in February 2024 with a team from UGA. Now we could better assess the pest management problems across disciplines and multiple crops.

At the conclusion of our visit in February, I asked Sparks, a professor in the UGA Department of Entomology, about his impressions of his visit to the Philippines.

“Though some in Georgia may wonder, there are many benefits from this visit to the Philippines. For example, we were able to see pests that we don’t have now but may have in the future. This visit gave me a greater appreciation for what we do in UGA Extension and the realization that many farmers in the world don't have access to such resources. I came away with a better appreciation for the knowledge level of our farmers. Visits to the Philippines and elsewhere undoubtedly enhance the reputation and influence of UGA,” Sparks replied.

Pauline Anderson, public affairs and assistant cultural affairs officer with the U.S. Embassy in the Philippines, emphasized the importance of the Fulbright Specialist Program.

“Farmers across the world are experiencing the challenges of a changing planet, and those changes are experienced very dramatically in the Philippines. Your work here gives you a front-row seat to witnessing the kinds of challenges Georgia farmers can anticipate, in addition to the challenges they are already familiar with,” Anderson wrote. “The more we see of the world, the more we realize that the specific challenges we face are not ours alone. You are bringing the experiences of the communities you serve to farmers in northern Luzon, and when you return home, you will bring some fresh perspectives you picked up here back to your home community.”

Anderson continued, “I am so happy that the Fulbright program brings you to the Philippines this year. You and I are both the custodians of a much longer-term relationship built on people-to-people ties between the United States and the Philippines going back more than a century.”

The U.S. Embassy signed its first agreements with MMSU in 1985, and the Fulbright Philippines program, which celebrates its 75th anniversary this year, is the longest uninterrupted Fulbright program in the world.

“It is the relationships that you build between farmers in northern Luzon and communities in Georgia that are going to sustain our agriculture and our common understandings about the world as we enter the middle years of the 21st century,” Anderson said.

I could not agree more. CAES allows us to work to make a difference on stages at home and around the world.

Kemerait and members of the UGA Peanut Team visit with farmers Benjamin and Eduardo Tabur, agricultural leaders in Santo Domingo, Ilocos Sur, Philippines, to consult on disease management for their peanut crop and pose for a selfie. (Photo by Bob Kemerait)

Kemerait and members of the UGA Peanut Team visit with farmers Benjamin and Eduardo Tabur, agricultural leaders in Santo Domingo, Ilocos Sur, Philippines, to consult on disease management for their peanut crop and pose for a selfie. (Photo by Bob Kemerait)

A Philippine flag flutters from a fence on Georgia farmland. (Photo by Bob Kemerait)

A Philippine flag flutters from a fence on Georgia farmland. (Photo by Bob Kemerait)

My Fulbright program focused on the improved production of high-value crops grown during the dry season, however my September arrival meant I was there during the wet season. Much of my first week and a half was characterized by torrential rains from a lingering typhoon that wandered just off the northern coast of Luzon. The weather was perfect for the rice, but not for a thorough assessment of the crops for which I was summoned. For this reason, I returned to MMSU and Ilocos Norte in February 2024 with a team from UGA. Now we could better assess the pest management problems across disciplines and multiple crops.

At the conclusion of our visit in February, I asked Sparks, a professor in the UGA Department of Entomology, about his impressions of his visit to the Philippines.

“Though some in Georgia may wonder, there are many benefits from this visit to the Philippines. For example, we were able to see pests that we don’t have now but may have in the future. This visit gave me a greater appreciation for what we do in UGA Extension and the realization that many farmers in the world don't have access to such resources. I came away with a better appreciation for the knowledge level of our farmers. Visits to the Philippines and elsewhere undoubtedly enhance the reputation and influence of UGA,” Sparks replied.

Pauline Anderson, public affairs and assistant cultural affairs officer with the U.S. Embassy in the Philippines, emphasized the importance of the Fulbright Specialist Program.

“Farmers across the world are experiencing the challenges of a changing planet, and those changes are experienced very dramatically in the Philippines. Your work here gives you a front-row seat to witnessing the kinds of challenges Georgia farmers can anticipate, in addition to the challenges they are already familiar with,” Anderson wrote. “The more we see of the world, the more we realize that the specific challenges we face are not ours alone. You are bringing the experiences of the communities you serve to farmers in northern Luzon, and when you return home, you will bring some fresh perspectives you picked up here back to your home community.”

Anderson continued, “I am so happy that the Fulbright program brings you to the Philippines this year. You and I are both the custodians of a much longer-term relationship built on people-to-people ties between the United States and the Philippines going back more than a century.”

The U.S. Embassy signed its first agreements with MMSU in 1985, and the Fulbright Philippines program, which celebrates its 75th anniversary this year, is the longest uninterrupted Fulbright program in the world.

“It is the relationships that you build between farmers in northern Luzon and communities in Georgia that are going to sustain our agriculture and our common understandings about the world as we enter the middle years of the 21st century,” Anderson said.

I could not agree more. CAES allows us to work to make a difference on stages at home and around the world.

My devotion as a UGA Extension specialist is to the agricultural community of our state; however I have the opportunity to work internationally … Whether for students or for faculty, UGA CAES provides opportunity on a global stage.

– Bob Kemerait

My devotion as a UGA Extension specialist is to the agricultural community of our state; however I have the opportunity to work internationally … Whether for students or for faculty, UGA CAES provides opportunity on a global stage.

– Bob Kemerait

Dig Deeper

For more than a century, researchers like Kemerait in UGA’s Department of Plant Pathology have been at the leading edge of knowledge and innovation. Their foundational scientific exploration helps safeguard crops, advance agricultural practices and ensure food security in Georgia and far beyond its borders.

News media may republish this story. A text version and art are available for download.