Mitigating a Perilous Flow

CAES researchers explore ways to abate PFAS in water and soil

In April 2024, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced the nation’s first drinking water standard for “forever chemicals,” a group of persistent, human-made chemicals that can pose a health risk to people at even the smallest detectable levels of exposure.

The new rules are part of efforts to limit pollution from these per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, which can persist in the environment for centuries.

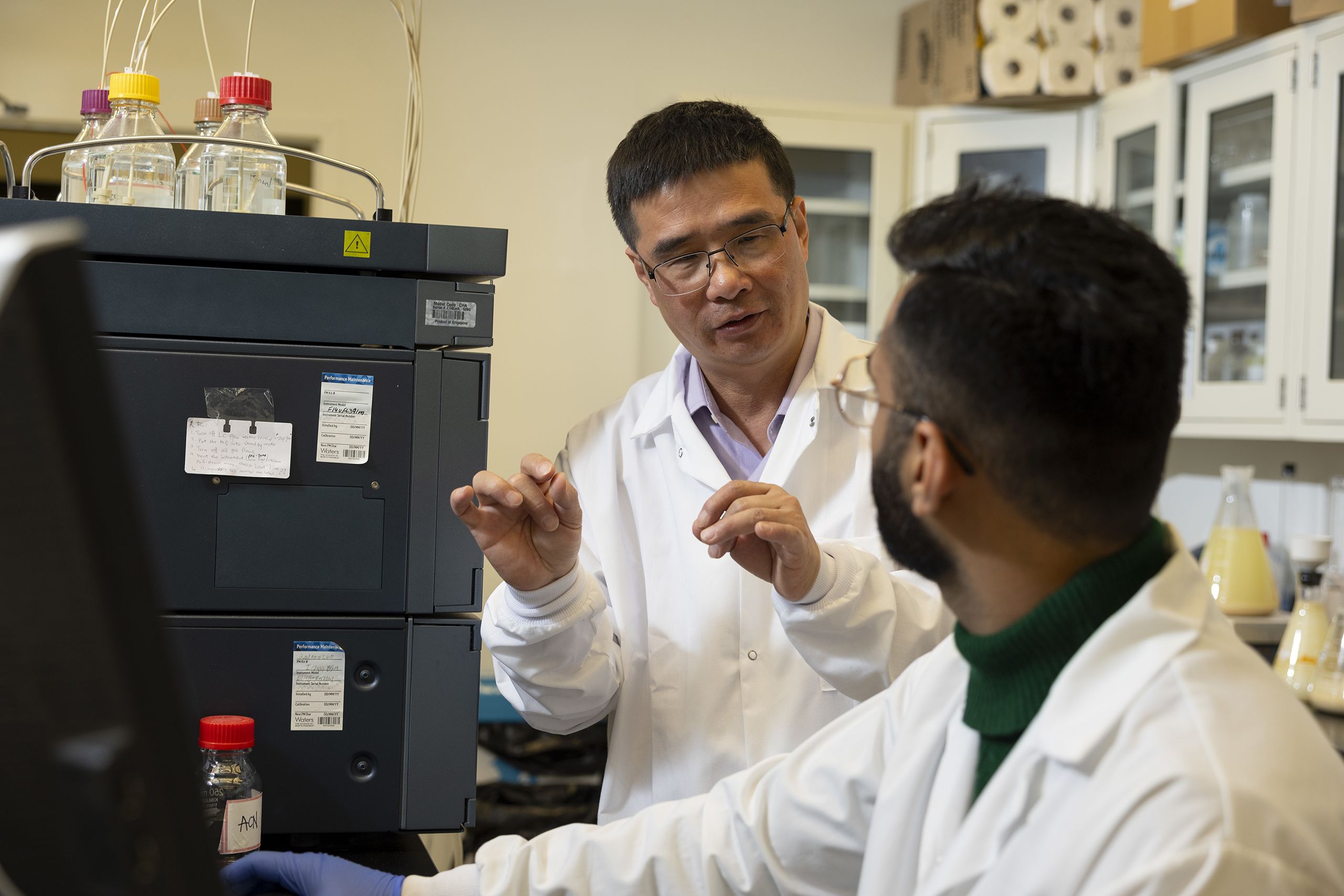

Supported by a nearly $1.6 million grant from the EPA, researchers from the University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences and UGA College of Engineering are developing improved, cost-effective treatment systems with advanced technologies for removing PFAS from water, wastewater and biosolids.

How PFAS cycle through the environment

Industry

For decades, PFAS were used in industry for firefighting foams and as a coating for waterproof, grease-proof and stain-resistant products.

PFAS exposure can happen through consuming contaminated water or food, breathing airborne PFAS, or working in occupations that use PFAS-containing products. Scientists are still determining the health effects of PFAS exposure and how they can bioaccumulate in human and animal body tissues.

Water treatment

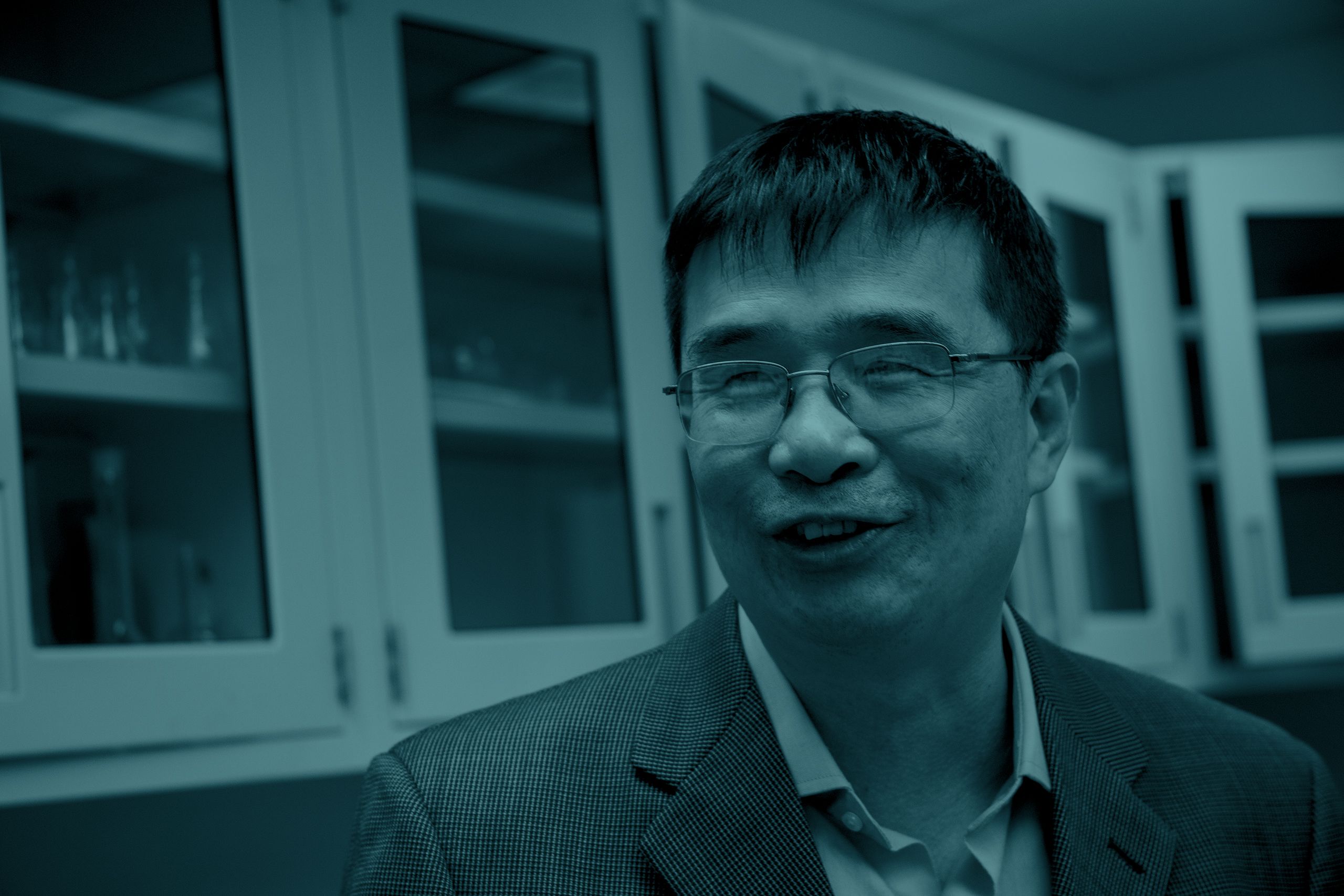

Professor Qingguo (Jack) Huang, primary investigator on the project, is working with colleagues to collect samples from wastewater treatment facilities, which act as the “sink” of a community — receiving and processing contaminants — making them an obvious place to look for these compounds.

Farms and consumers

PFAS first accumulate in the human gut as we are exposed to the compounds. Humans shed some of those compounds through waste, which collects at treatment facilities. After a multistage clarification process, treated water eventually makes its way to streams and rivers or agricultural land-application systems. These surface waters often become the source of another city’s drinking water, making it critical to understand how to best manage PFAS in wastewater.

Permeating Products

There are more than 9,000 known PFAS, yet common testing methods can identify only a couple dozen.

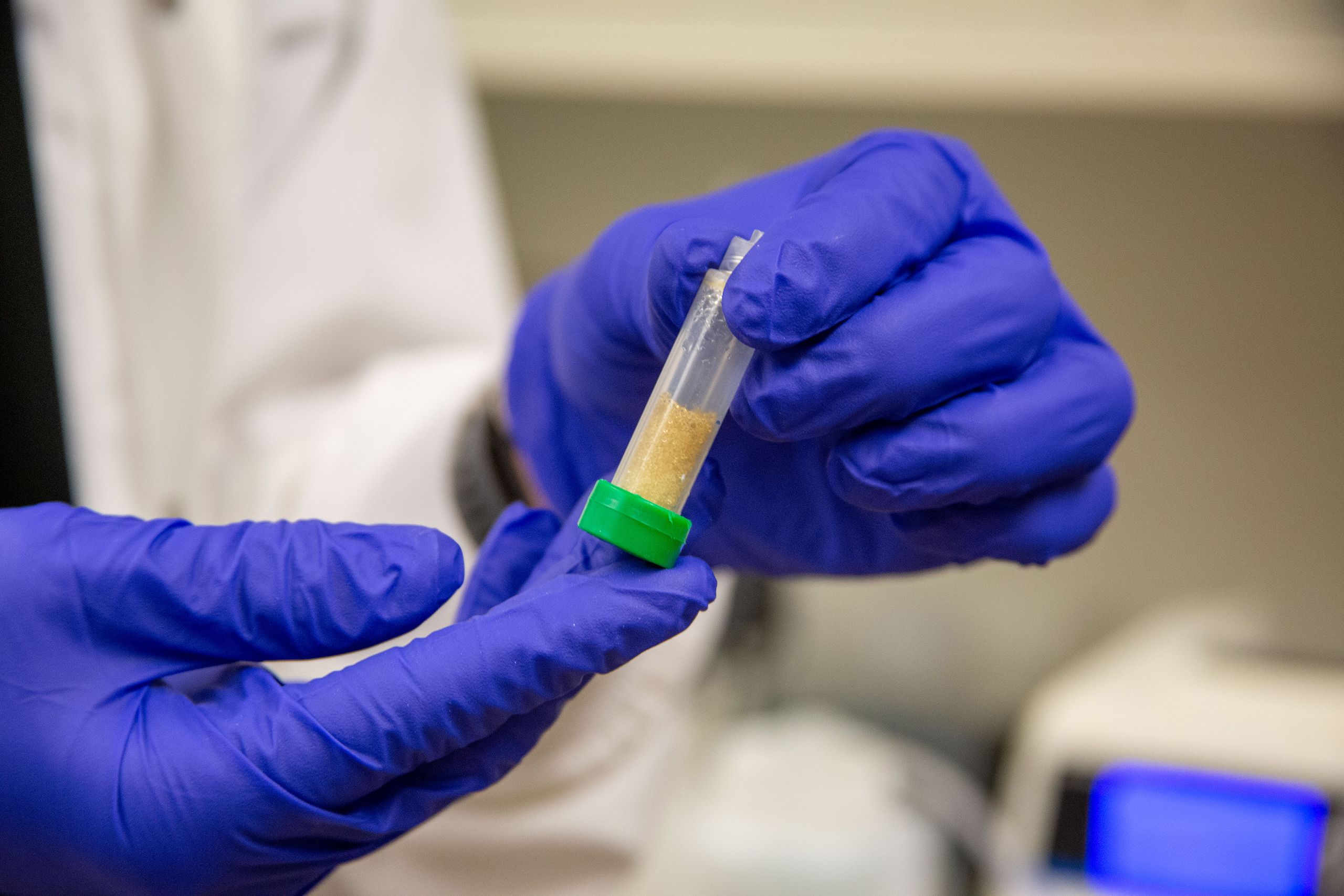

The extreme chemical and physical stability of PFAS is key to their appeal as an ingredient in consumer products. This also makes the compounds extremely slow to degrade once they have entered the environment, earning the moniker “forever chemicals.” The team continues investigating enzymes and fungal strains that essentially devour PFAS compounds in hopes that they can facilitate faster breakdown of PFAS in soil and reduce concentrations over time.

What materials can contain PFAS?

Industrial products: firefighting foam, water-resistant fabrics and stain-resistant coatings

Household products: cleaning products, grease-resistant paper and nonstick cookware

Personal care products: shampoo, dental floss, nail polish and eye makeup

Food packaging: fast-food wrappers, can linings, compostable takeout containers, microwavable popcorn bags and pet food bags

“We are especially proud that CAES research will provide some cost-effective solutions to combat PFAS water contamination, particularly for rural areas. As researchers, it’s important to keep pushing the boundary. To drive forward, you have to have the vision of what is needed.”

– Jack Huang