Journey to Work

Georgia is consistently one of the top five states to use the H-2A visa program and depends on H-2A workers for 60% of agricultural jobs.

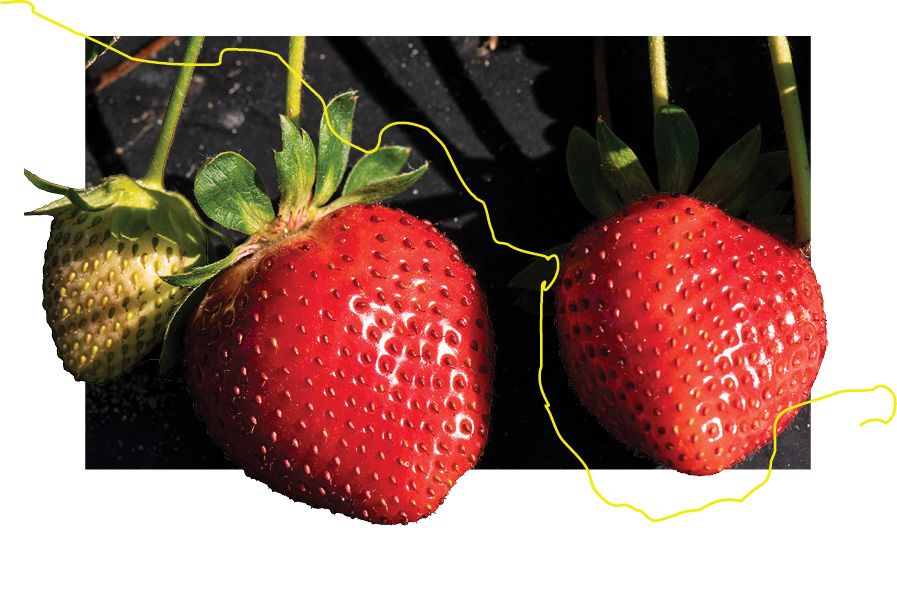

On a farm in southwest Georgia, the rising sun is just beginning to shine upon acres of lush fall crops growing in neat rows. Migrant workers are hunched over, quickly picking the dew-covered leafy greens destined for grocery stores throughout the country.

At the end of a hard day, they head home to a shared house that has been provided to them for the duration of their employment. The next morning, they will wake and return to the fields for another day of work in the elements and finish with a shared evening in the communal housing.

This has been the workers’ routine throughout the warm season. They will harvest crops into late fall, when they will finally pack up and return to their home countries to seek out local work while they wait for the growing season to begin again in the United States.

A similar story plays out each year for more than 350,000 migrant workers in the U.S. who participate in the H-2A Temporary Agricultural Workers Program, often called the H-2A visa program. The program helps U.S. farmers temporarily fill employment gaps for planting, cultivating and harvesting crops when domestic workers are in short supply, primarily in the more labor-intensive fruit, vegetable and horticulture industries.

“When you look at the states with the highest utilization of the H-2A program, you see it’s consistently states in the Southeast, of which Georgia is one of the highest employers of these workers every year,” said Cesar Escalante, a professor in the Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics at the University of Georgia’s College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences.

Farms in the Southeast tend to be smaller than other regions due to the varied topography and watersheds that branch into rivers and streams, creating natural breaks in arable land. Coupled with the warm, wet climate, fruits and vegetables are a mainstay for the region’s economy. For these reasons, farms are less mechanized than those in the Midwest, and labor demands are higher.

H-2A visas and wage adjustments

Before a job can be certified for the H-2A program, the U.S. Department of Labor requires employers to demonstrate that their efforts to recruit U.S. workers have been unsuccessful. Despite these restrictions, the H-2A program has grown rapidly in recent years as domestic workers find jobs outside agriculture.

Georgia is consistently one of the top five states to use the program, depending on H-2A workers for 60% of agricultural jobs. Last year, the Department of Labor passed legislation to raise the Adverse Effect Wage Rate (AEWR) by a sharp 14% for several states, including Georgia.

The AEWR establishes the minimum wage for H-2A workers and serves as a benchmark to ensure their wages would not cause a downward market pressure on U.S. wages of workers in similar occupations. With the minimum wage increased to almost $14 per hour, coming on the heels of a near 10% increase in 2022, there is additional pressure on farm owners whose main cost of operation tends to be labor.

Wage increases and the bottom line

For 20-plus years, Escalante has sought to help both farm owners and the workers they employ become more successful.

The H-2A program is already an expensive program for farmers to fund, said Escalante, a fact compounded by current economic pressures and record-high input costs. The drastic wage increase puts a lot of small- to mid-scale farmers at risk of having to make significant economic sacrifices or losing their farm businesses altogether.

The crux of Escalante’s work is supporting the interests of farm businesses while also valuing and fairly compensating the people doing the labor in the field.

Currently, Escalante is investigating whether increased patronage in the H-2A program and wage rates have any impact on farm businesses’ bottom lines. His research will focus on fruit and vegetable farms and will estimate how profits are affected. He will also determine whether there have been any adjustments in operating strategies made to cope with increasing input costs.

Effects of immigration policy

For decades, economists have studied the impact of immigration on domestic labor markets. As a shortage of domestic farm labor has led to increased participation in the H-2A visa program, a brief look back at past immigration policies helps frame why migrants from Central and South America have largely been associated with filling necessary agricultural jobs in the U.S.

The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) of 1952 authorized the H-2 nonimmigrant visa category — the precursor to the H-2A program — which officially permitted the recruitment of temporary foreign farmworkers to the U.S.

Fast forward to 1996, when the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act added Section 287(g) to the Immigration and Nationality Act. Often referred to simply as 287(g)s, the provision authorized U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement to partner with state and local law enforcement agencies to perform immigration officer functions under the agency’s direction and oversight, explained Genti Kostandini, a professor of agricultural and applied economics at CAES.

After the attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, immigration policies were swiftly updated to enact even stricter enforcement of undocumented immigrants, whether or not they had committed a crime.

Following the economic downturn in 2008, that nationalistic sentiment pervaded domestic politics. In 2009, then-President George W. Bush signed an executive order requiring all federal contractors and subcontractors to use a previously voluntary program, called E-Verify, which required employers to confirm that all employees were legally registered to work in the U.S. The combination of 287(g)s and the use of E-Verify established a structure in the labor market intended to provide more economic opportunity and growth for communities, particularly for U.S. citizens.

Impact of immigration enforcement

While these policies were intended to root out undocumented immigrants, they often produced complications for documented immigrants as well. The fear of being deported was a strong driver for immigrants to move to jurisdictions that did not enforce such strong immigration policies, Kostandini explained.

In a collaborative study of the impact 287(g) policies have on agriculture in the U.S., Kostandini and Escalante found a marked reduction in immigrant presence in jurisdictions where these policies were adopted. However, there was also a noticeable reduction in overall farm profitability. A similar study found E-Verify produced comparable results.

“We found that … at least for agriculture, these programs didn’t do anything in terms of wages, increased employment or career advancement opportunities for U.S. citizens, for whose benefit they were created,” said Kostandini, explaining that farms that were in either 287(g) or E-Verify jurisdictions realized lower overall profits.

The research also followed the trends of undocumented versus documented immigrants. In counties with these policies, there were fewer undocumented immigrants; however, instead of seeing increased job placement of U.S. citizens in agricultural jobs, documented immigrants benefited from the policies, further demonstrating that citizen workers are not pursuing the types of agricultural jobs undocumented workers do.

In 2011, a comprehensive statewide survey conducted by the UGA Center for Agribusiness and Economic Development revealed that millions of dollars in crop losses and tens of thousands of farming jobs were being left unfilled in the wake of these restrictive policies.

“Ultimately, I hope these workers will be seen as a valued asset to the country’s rich and diverse national history.”

Smaller farms struggle

Escalante said years of research have shown that farm owners and managers struggle to fill fieldwork positions with domestic workers, who seek jobs that provide better pay, overtime, insurance and fringe benefits, as well as less risk of physical injury and exposure to environmental risks.

In 2020, an estimated 70% of farmworkers in the country were from Central America, according to the U.S. Department of Labor.

When looking at the big picture, Escalante said the farms most impacted by restrictive immigration policies are smaller farms, which are more labor intensive, as larger farm operations are better suited to mechanize in the absence of manual labor.

Improving the H-2A program

In the halls of Congress, legislators are working together to provide legal pathways for improving the H-2A program to offer growers a viable and sustainable process for employing these necessary workers each year.

For thousands of hardworking men and women who rely on the H-2A program, and for the survival of U.S. agriculture, Escalante hopes more researchers and interest groups will conduct timely and crucial work in this area.

“This is a tough issue,” he said, “Tension is high right now for many people struggling to make a living, but ultimately, I hope these workers will be seen as a valued asset to the country’s rich and diverse national history.”